tcgen05 for dummies

tcgen05 is the set of PTX instructions to program Tensor Cores on the latest NVIDIA Blackwell GPUs (sm100, not to be confused with consumer Blackwell sm120). At the time of writing, I couldn’t find a Blackwell tutorial in plain CUDA C++ with PTX, even though such exist for Ampere (alexarmbr’s and spatters’) and Hopper (Pranjal’s). So let’s write one, documenting my process of learning tcgen05 and reaching 98% of CuBLAS speed (on M=N=K=4096 problem shape)!

All B200 work was done on Modal, which provides a very convenient platform to run short-lived functions, such as implementing a Blackwell matmul kernel like what we are doing here. Feel free to follow along the article using Modal, or any other B200 cloud providers.

You can find the code here: https://github.com/gau-nernst/learn-cuda/tree/3b90ac9b/02e_matmul_sm100/

Recap on writing a performant matmul kernel

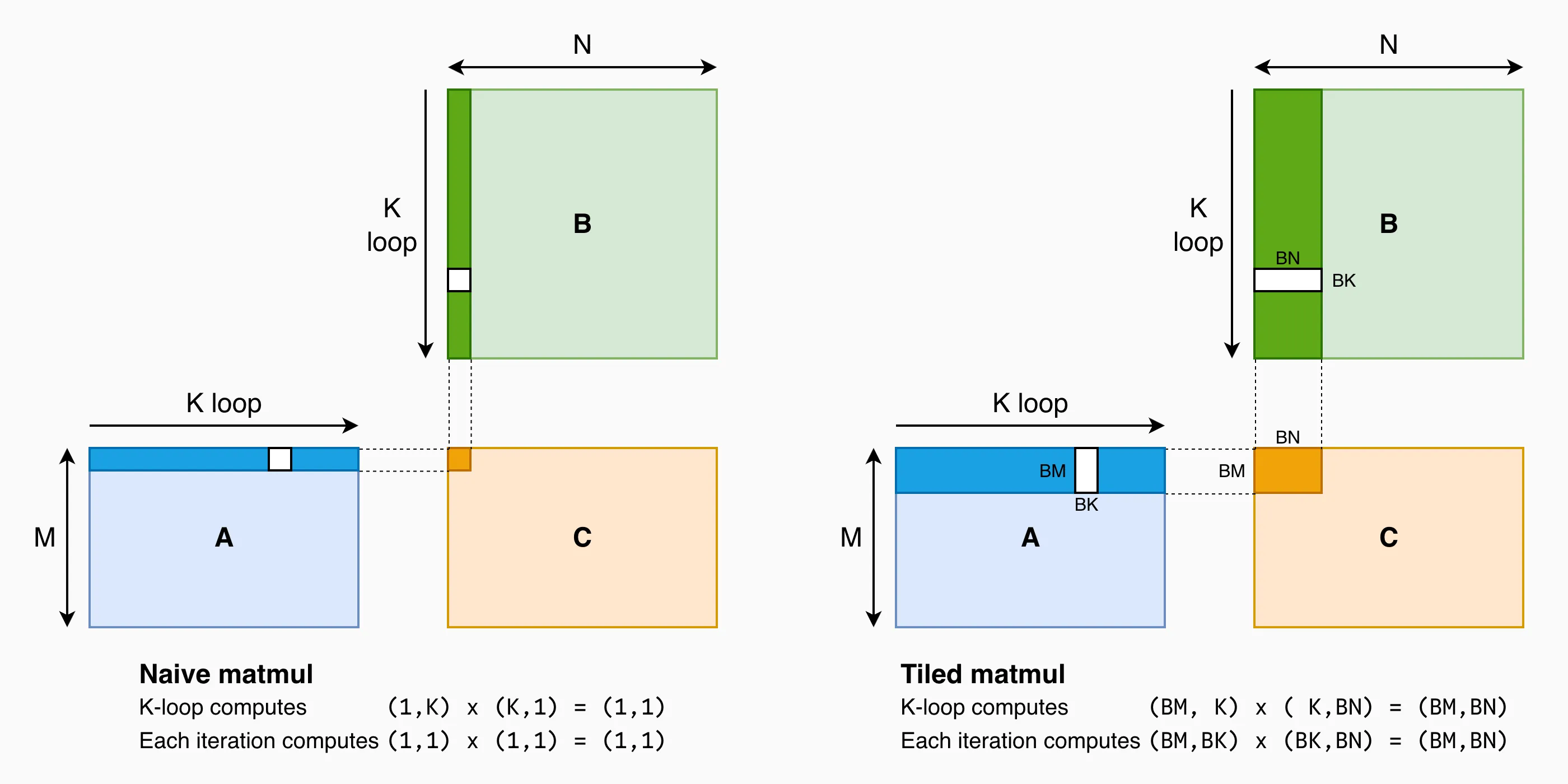

Matrix multiplication between A (of shape MxK) and B (of shape KxN) produces the output C with shape MxN. Mathematically, each element of C is a dot product between a row of A and a column of B.

def matmul(A: Tensor, B: Tensor, C: Tensor, M: int, N: int, K: int):

for m in range(M):

for n in range(N):

# initialize accumulator

acc = 0

# doing dot product along K

for k in range(K):

acc += A[m, k] * B[k, n]

# store result

C[m, n] = acc

However, pretty much all matmul implementations do some form of tiling, instead of computing the dot product directly. Tiling selects a block of A and B, compute a mini-matmul on it, and accumulate the result along the K dimension. In fact, this can still be seen as doing dot product, but with a tile granularity instead of element granularity.

def tiled_matmul(A: Tensor, B: Tensor, C: Tensor, M: int, N: int, K: int):

BLOCK_M = 128

BLOCK_N = 128

BLOCK_K = 64

for m in range(0, M, BLOCK_M):

for n in range(0, N, BLOCK_N):

# initialize accumulator

acc = torch.zeros(BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N)

# doing mini matmuls along K

for k in range(0, K, BLOCK_K):

# select tiles of A and B

A_tile = A[m:m+BLOCK_M, k:k+BLOCK_K] # shape [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K]

B_tile = B[k:k+BLOCK_K, n:n+BLOCK_N] # shape [BLOCK_K, BLOCK_N]

acc += mini_matmul(A_tile, B_tile) # shape [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N]

# store result

C[m : m + BLOCK_M, n : n + BLOCK_N] = acc

Illustration of naive matmul (left) and tiled matmul (right).

There are many good reasons why tiled matmul is better than the naive implementation on modern processors, but I’m going to give you a dumb reason: Tensor Cores is our mini-matmul engine, hence it is natural to “tile” our problem according to the shapes of Tensor Cores. In practice, there can be multiple levels of tiling, each trying to exploit certain hardware characteristics.

The Python code above forms the high-level structure of our matmul GPU kernel. The m- and n- loops are parallelized across threadblocks i.e. each threadblock is responsible for BLOCK_M x BLOCK_N of output, and it reads BLOCK_M x K of A and K x BLOCK_N of B. Within each threadblock, we iterate along the K dimension, load tiles of A and B, and compute matrix-multiply and accumulate (MMA) using Tensor Cores. Each generation of NVIDIA GPUs has their own set of PTX instructions to perform load and compute.

| Generation | Load | Compute |

|---|---|---|

| Ampere (sm80) | cp.async | mma |

| Hopper (sm90) | cp.async.bulk.tensor (TMA) | wgmma.mma_async |

| Blackwell (sm100) | cp.async.bulk.tensor (TMA) | tcgen05.mma |

Conceptually, a Blackwell matmul kernel is not much different from those of previous generations. We only need to understand the new PTX instructions to unlock the hardware’s FLOPS. Let’s dive into the first one - cp.async.bulk.tensor for the TMA.

Basic tcgen05 kernel

TMA and mbarrier for dummies

Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) is the new cool hardware, existing since Hopper, to issue memory loads with minimal register usage and address calculations. Previously, cp.async can only issue at most 16-byte load per thread. In contrast, TMA can issue loads of arbitrary sizes, using only 1 thread. In PTX, TMA corresponds to cp.async.bulk (1D tile) and cp.async.bulk.tensor (1D to 5D tile) instructions.

First, we need to create a Tensor Map object to encode how we want TMA to transfer the data from global to shared memory (you can do the reverse direction as well, from shared to global memory). This needs to be done on the host side, using CUDA Driver API.

#include <cudaTypedefs.h> // required for CUtensorMap

#include <cuda_bf16.h>

constexpr int BLOCK_M = 64;

constexpr int BLOCK_N = 64;

constexpr int BLOCK_K = 64;

constexpr int TB_SIZE = 128;

__global__

void kernel(

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap A_tmap,

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap B_tmap,

nv_bfloat16 *C_ptr,

int M, int N, int K

) {

... // we will cover this later.

}

// forward declaration. we will cover this later.

void init_2D_tmap(

CUtensorMap *tmap,

const nv_bfloat16 *ptr,

uint64_t global_height, uint64_t global_width,

uint32_t shared_height, uint32_t shared_width

);

void launch(

const nv_bfloat16 *A_ptr,

const nv_bfloat16 *B_ptr,

nv_bfloat16 *C_ptr,

int M, int N, int K

) {

// prepare tensor map objects on the host.

CUtensorMap A_tmap, B_tmap;

init_2D_tmap(&A_tmap, A_ptr, M, K, BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K);

init_2D_tmap(&B_tmap, B_ptr, N, K, BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K);

const dim3 grid(N / BLOCK_N, M / BLOCK_M);

// 1 A tile [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K] and 1 B tile [BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K]

const int smem_size = (BLOCK_M + BLOCK_N) * BLOCK_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

kernel<<<grid, TB_SIZE, smem_size>>>(A_tmap, B_tmap, C_ptr, M, N, K);

}

We use const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap as the qualifier and type for kernel arguments, and pass them to the kernel as usual. As you may notice, we are assuming both A and B are K-major, as we are referring to the shapes of A and B as (M, K)/(BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K) and (N, K)/(BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K) respectively. This makes things easier later, and it also aligns with how nn.Linear() layer is commonly used in PyTorch: (contiguous) inputs have shape (batch_size, in_features), (contiguous) weights have shape (out_features, in_features), and the layer computes Y = X @ W.T.

init_2D_tmap() is a small wrapper around cuTensorMapEncodeTiled(), which defines the global and shared memory layout i.e. shape and stride.

Parameters involved in a Tensormap object. globalDim, globalStrides, and boxDim are encoded inside the Tensormap object, while tensorCoords are supplied at runtime to cp.async.bulk.tensor to select the 2D tile.

void init_2D_tmap(

CUtensorMap *tmap,

const nv_bfloat16 *ptr,

uint64_t global_height, uint64_t global_width,

uint32_t shared_height, uint32_t shared_width

) {

constexpr uint32_t rank = 2;

// ordering of dims and strides is reverse of the natural PyTorch's order.

// 1st dim is the fastest changing dim.

uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {global_width, global_height};

// global strides are in bytes.

// additionally, the 1st dim is assumed to have stride of 1-element width.

uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {global_width * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)};

// shape in shared memory

uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {shared_width, shared_height};

uint32_t elementStrides[rank] = {1, 1};

auto err = cuTensorMapEncodeTiled(

tmap,

CUtensorMapDataType::CU_TENSOR_MAP_DATA_TYPE_BFLOAT16,

rank,

(void *)ptr,

globalDim,

globalStrides,

boxDim,

elementStrides,

// you can ignore the rest for now

CUtensorMapInterleave::CU_TENSOR_MAP_INTERLEAVE_NONE,

CUtensorMapSwizzle::CU_TENSOR_MAP_SWIZZLE_NONE,

CUtensorMapL2promotion::CU_TENSOR_MAP_L2_PROMOTION_NONE,

CUtensorMapFloatOOBfill::CU_TENSOR_MAP_FLOAT_OOB_FILL_NONE

);

// check the returned error code

}

Now, we are ready to use the tensor map in the kernel. I don’t really like this section in the CUDA C++ docs as it feels overly verbose. Instead, let’s continue with the PTX docs.

- It’s quite funny that there is no mention of TMA at all in the PTX docs. The reader is expected to know that

cp.async.bulkcorresponds to the TMA, though it may make sense that PTX abstracts away the hardware implementation. - Still, having links across abstraction layers makes it easier to connect the dots, similar to how PTX doc directly refers to CuTe layouts.

TMA operates in the async proxy. I won’t pretend I understand what async proxy means, but my mental model of it is that TMA is a separate device from the perspective of programming the CUDA cores. It means that whenever we read data written by TMA, or write data to be read by TMA, we need to follow PTX memory cosistency model and perform the necessary memory synchronizations.

These are big words and I don’t thinking reading such topics straight from the PTX doc is helpful for beginners. What you need to know (for now) is that NVIDIA provides mbarrier as the mechanism to synchronize with the TMA correctly. Using TMA inside your kernel looks something like this.

__device__ inline

void tma_2d_gmem2smem(int dst, const void *tmap_ptr, int x, int y, int mbar_addr) {

asm volatile("cp.async.bulk.tensor.2d.shared::cta.global.mbarrier::complete_tx::bytes [%0], [%1, {%2, %3}], [%4];"

:: "r"(dst), "l"(tmap_ptr), "r"(x), "r"(y), "r"(mbar_addr) : "memory");

}

__global__

void kernel(

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap A_tmap,

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap B_tmap,

nv_bfloat16 *C_ptr,

int M, int N, int K

) {

const int tid = threadIdx.x;

const int bid_n = blockIdx.x;

const int bid_m = blockIdx.y;

// select the input and output tiles

const int off_m = bid_m * BLOCK_M;

const int off_n = bid_n * BLOCK_N;

// set up smem

// alignment is required for TMA

extern __shared__ __align__(1024) char smem[];

const int A_smem = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(smem));

const int B_smem = A_smem + BLOCK_M * BLOCK_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

// set up mbarriers. to be covered

#pragma nv_diag_suppress static_var_with_dynamic_init

__shared__ uint64_t mbars[1];

const int mbar_addr = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(mbars));

...

// main loop, iterate along K dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < K / BLOCK_K; iter_k++) {

// only 1 thread in a threadblock issues TMA

if (tid == 0) {

// specify the offsets in global memory to select the 2D tile to be copied.

// note that K dim goes first, since it's the contiguous dim.

const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K;

tma_2d_gmem2smem(A_smem, &A_tmap, off_k, off_m, mbar_addr);

tma_2d_gmem2smem(B_smem, &B_tmap, off_k, off_n, mbar_addr);

// inform mbarrier how much data (in bytes) to expect.

// (and the TMA-issuing thread also "arrives" at the mbarrier - to be covered)

constexpr int cp_size = (BLOCK_M + BLOCK_N) * BLOCK_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

asm volatile("mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx.release.cta.shared::cta.b64 _, [%0], %1;"

:: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(cp_size) : "memory");

}

// wait for TMA to finish. to be covered

...

// issue tcgen05.mma. to be covered

...

}

}

That’s a lot more things to be covered, but I hope you get the high-level idea before zooming in to the details. Issuing TMA is the easy part - simply sprinkle some cp.async.bulk.tensor. It’s more important that we understand mbarrier and how to use it correctly.

- There will be a lot of references to PTX instructions. To learn more about any of them, just go to PTX doc and Ctrl+F for that instruction.

mbarrier resides in shared memory, and is 64-bit / 8-byte wide. You can treat it as an opaque object, since NVIDA may change its internal bit fields implementation in future generations. mbarrier keeps track of 2 counts: arrival count (roughly how many threads have “arrived”) and tx-count (how many bytes have been transferred).

- We set the expected arrival count at

mbarrierinitialization. This is usually the number of producer threads for a particular synchronization point. For TMA, since only 1 thread issues TMA, we will initialize thembarrierwith 1. - Whenver we perform an arrive-on operation, the pending arrival count is decremented. Some examples of arrive-on operations are

mbarrier.arriveandtcgen05.commit.mbarrier::arrive::one. - tx-count is more flexible. We can increment it with expect-tx operation e.g.

mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx(which also decrements pending arrival count at the same time), and decrement it with complete-tx operation e.g.cp.async.bulk.shared::cta.global.mbarrier::complete_tx::bytes. - When BOTH pending arrival count and tx-count reach zero, the current phase is complete, and the

mbarrierobject immediately moves on to the next (incomplete) phase.

Let’s put this in action. This is how we initialize the mbarrier for TMA synchronization.

// only 1 thread initializes mbarrier

if (tid == 0) {

// initialize with 1, since only 1 thread issue TMA

asm volatile("mbarrier.init.shared::cta.b64 [%0], %1;" :: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(1));

asm volatile("fence.mbarrier_init.release.cluster;"); // initialized mbarrier is visible to async proxy

}

__syncthreads(); // initialized mbarrier is visible to all threads in the threadblock

Note that __syncthreads() is a memory barrier - it ensures all memory accesses, initializing mbarrier in shared memory in this case, issued by all threads (in the threadblock) are visible to all other threads (in the same threadblock).

We know how to issue TMA, and signals to the mbarrier, as shown above. Waiting for TMA to finish is equivalent to waiting for mbarrier to complete its current phase. However, instead of using the phase 0, 1, 2, 3, … directly, we use the phase parity i.e. 0 or 1.

// initial phase parity to wait for

int phase = 0;

// main loop, iterate along K dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < K / BLOCK_K; iter_k++) {

// issue TMA

...

// wait for mbarrier to complete the current phase

mbarrier_wait(mbar_addr, phase);

// flip the phase parity, so that we wait for the correct parity in the next iteration

phase ^= 1;

// issue tcgen05.mma

...

}

mbarrier_wait() is basically spinning on the barrier.

// https://github.com/NVIDIA/cutlass/blob/v4.2.1/include/cutlass/arch/barrier.h#L408

__device__ inline

void mbarrier_wait(int mbar_addr, int phase) {

uint32_t ticks = 0x989680; // this is optional

asm volatile(

"{\n\t"

".reg .pred P1;\n\t"

"LAB_WAIT:\n\t"

"mbarrier.try_wait.parity.acquire.cta.shared::cta.b64 P1, [%0], %1, %2;\n\t"

"@P1 bra.uni DONE;\n\t"

"bra.uni LAB_WAIT;\n\t"

"DONE:\n\t"

"}"

:: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(phase), "r"(ticks)

);

}

The scary-looking snippet above is a loop in PTX.

.reg .pred P1;declares a predicate register, holding either 0 or 1.@P1is predicated execution: only whenP1=1, we will branch (uniformly i.e. all active threads in a warp) to the labelDONE. Otherwise, we will branch back toLAB_WAIT.

Putting all together, our code for TMA looks like this.

// set up mbarriers

#pragma nv_diag_suppress static_var_with_dynamic_init

__shared__ uint64_t mbars[1];

const int mbar_addr = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(mbars));

if (tid == 0) {

asm volatile("mbarrier.init.shared::cta.b64 [%0], %1;" :: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(1));

asm volatile("fence.mbarrier_init.release.cluster;"); // visible to async proxy

}

__syncthreads(); // visible to all threads in the threadblock

// initial phase

int phase = 0;

// main loop, iterate along K dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < K / BLOCK_K; iter_k++) {

// only 1 thread in a threadblock issues TMA

if (tid == 0) {

const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K;

tma_2d_gmem2smem(A_smem, &A_tmap, off_k, off_m, mbar_addr);

tma_2d_gmem2smem(B_smem, &B_tmap, off_k, off_n, mbar_addr);

constexpr int cp_size = (BLOCK_M + BLOCK_N) * BLOCK_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

asm volatile("mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx.release.cta.shared::cta.b64 _, [%0], %1;"

:: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(cp_size) : "memory");

}

// wait for TMA to finish.

mbarrier_wait(mbar_addr, phase);

phase ^= 1; // flip phase parity

// issue tcgen05.mma. to be covered

...

}

It doesn’t look too cumbersome to use TMA now isn’t it. Just a few PTX instructions (and some annoying setup on the host).

Acquire-Release semantics

Before moving on to tcgen05, I want to spend some time talking about Acquire-Release semantics. In case you haven’t noticed, we have already used Acquire-Release semantics extensively.

mbarrier.try_wait.parity{.acquire}.cta.shared::cta.b64mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx{.release}.cta.shared::cta.b64

I purposely made it explicit to include .acquire and .release, even when those modifiers are optional (the instruction defaults to the correct semantic anyway). This comes from my past experience writing multi-GPU HIP kernels, where Acquire-Release semantics are also crucial in synchronizing memory accesses across GPUs. I explained it in more details in my previous blog post. Or you can also refer to this beautifully written post by Dave Kilian.

In short, an Acquire-Release pair makes sure that anything BEFORE Release (on producer thread) is visible to everything AFTER Acquire (on consumer thread). In the context of TMA, it means that once we finish mbarrier_wait() (i.e. mbarrier.try_wait returns 1), we are confident that TMA transfers have finished, and any subsequent operations touching shared memory (e.g. tcgen05.mma, or even just loading data from shared memory ld.shared) see fresh data.

Acquire-Release semantics for TMA producer and tcgen05 consumer.

This is also confirmed again in the mbarrier.try_wait section of the PTX doc (look for the phrase “The following ordering of memory operations…”).

All

cp.async.bulkasynchronous operations using the same mbarrier object requested prior, in program order, tombarrier.arrivehaving release semantics during the completed phase by the participating threads of the CTA are performed and made visible to the executing thread.

There is no ordering and visibility guarantee for memory accesses requested by the thread after

mbarrier.arrivehaving release semantics and prior tombarrier.test_wait, in program order.

Decipher tcgen05

The table below gives an overview on some of the differences in the MMA instructions across GPU generations.

| Generation | MMA instruction | A/B memory | C/D memory | Max BF16 MMA shape (per CTA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampere (sm80) | mma | Registers | Registers | m16n8k16 |

| Hopper (sm90) | wgmma.mma_async | Shared memory | Registers | m64n256k16 |

| Blackwell (sm100) | tcgen05.mma | Shared memory(*) | Tensor memory | m128n256k16 |

(*) On Blackwell, A can also be in Tensor memory.

- Interestingly,

MMA_Kremains 32-byte whileMMA_MandMMA_Nincrease significantly. It makes sense because this trend improves arithmetic intensity of the MMA instruction, ensuring faster compute won’t be bottlenecked by memory.

We know how to load A and B to shared memory using TMA, and there is no need to load them to registers as tcgen05.mma operates directly on shared memory (say goodbye to ldmatrix). To hold MMA results, we need to use Tensor memory, a new kind of memory in Blackwell dedicated to this purpose. Tensor memory has the capacity of 128x512, where each element is 32-bit wide, just right for storing FP32 or INT32 accumulation. Using it is quite straightforward:

- Allocation (

tcgen05.alloc) in the granularity of columns. In other words, all 128 rows are always allocated. - Deallocation (

tcgen05.dealloc). You HAVE TO deallocate a previous allocation before kernel exit. The kernel won’t do it automatically for you. - Various memory access options:

tcgen05.ld: tensor memory to registers - We will use this for writing the epilogue later.tcgen05.st: registers to tensor memory.tcgen05.cp: shared memory to tensor memory.

Adding Tensor memory allocation and deallocation to our code looks like this.

#pragma nv_diag_suppress static_var_with_dynamic_init

__shared__ uint64_t mbars[1];

__shared__ int tmem_addr[1]; // tmem address is 32-bit

if (tid == 0) {

// lane0 of warp0 initializes mbarriers (1 thread)

asm volatile("mbarrier.init.shared::cta.b64 [%0], %1;" :: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(1));

asm volatile("fence.mbarrier_init.release.cluster;");

} else if (warp_id == 1) {

// one full warp allocates tmem

// tcgen05.alloc returns tmem address in shared memory

// -> we provide an smem address to the instruction.

const int addr = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(tmem_addr));

asm volatile("tcgen05.alloc.cta_group::1.sync.aligned.shared::cta.b32 [%0], %1;" :: "r"(addr), "r"(BLOCK_N));

}

// making not only initialized mbarriers, but also the allocated tmem,

// visible to all threads in the threadblock.

__syncthreads();

// read tmem address, which has the value of 0.

const int taddr = tmem_addr[0];

// main loop

...

// make sure epilogue finishes using tmem

...

// tmem deallocation is also issued by one full warp

if (warp_id == 0)

asm volatile("tcgen05.dealloc.cta_group::1.sync.aligned.b32 %0, %1;" :: "r"(taddr), "r"(BLOCK_N));

- The output tile has shape

[BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N], so we are allocatingBLOCK_Ncolumns, assumingBLOCK_M <= 128. - From my experience,

taddris always zero, at least when doing only 1 allocation in the kernel’s lifetime. Therefore, you can pretty much ignore the returned value oftcgen05.alloc, and assume it to be 0.

Moving on to the highly anticipated MMA instruction. I take this directly from the PTX doc of tcgen05.mma.

tcgen05.mma.cta_group.kind [d-tmem], a-desc, b-desc, idesc,

{ disable-output-lane }, enable-input-d {, scale-input-d};

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

d-tmem | Tensor memory address we have obtained above. To hold accumulator. |

a-desc and b-desc | Shared memory descriptors (64-bit), describing the layouts of A and B in shared memory. |

idesc | Instruction descriptor (32-bit), encoding various attributes of the MMA instruction (e.g. dtypes, MMA shape, dense or sparse, …) |

enable-input-d | A predicate register indicating whether to do accumulation i.e. D = A @ B vs D = A @ B + C. |

scale-input-d | Can be ignored, not important for us. |

idesc is simple as the PTX doc provides a pretty self-explanatory table. Refer to that if you need more information.

constexpr uint32_t i_desc = (1U << 4U) // dtype=FP32

| (1U << 7U) // atype=BF16

| (1U << 10U) // btype=BF16

| ((uint32_t)BLOCK_N >> 3U << 17U) // MMA_N

| ((uint32_t)BLOCK_M >> 4U << 24U) // MMA_M

;

tcgen05supports large MMA shapes, so I find no reason to do MMA tiling overBLOCK_M/BLOCK_N, at least at this stage. It means we can setBLOCK_Mto 128, andBLOCK_Ncan be anything up to 256.

a-desc and b-desc are, strange. Instead of explaining them now, we move on to the overall structure of using tcgen05.mma. Similar to TMA, tcgen05.mma is issued using only one thread. To track the completion of a series of tcgen05.mma, we use tcgen05.commit together with an mbarrier object.

// main loop, iterate along K dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < K / BLOCK_K; iter_k++) {

// only 1 thread in a threadblock issues TMA

if (tid == 0) {

...

}

// wait for TMA to finish.

mbarrier_wait(mbar_addr, phase);

phase ^= 1; // flip phase parity

// not sure if we need this. taken from DeepGEMM

// https://github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepGEMM/blob/9b680f42/deep_gemm/include/deep_gemm/impls/sm100_bf16_gemm.cuh#L289

asm volatile("tcgen05.fence::after_thread_sync;");

// only 1 thread issues tcgen05.mma

if (tid == 0) {

auto make_desc = [](int addr) -> uint64_t {

// to be implemented

...

};

// manually unroll 1st iteration to disable accumulation

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, make_desc(A_smem), make_desc(B_smem), i_desc, iter_k);

for (int k = 1; k < BLOCK_K / MMA_K; k++) {

// select MMA tile of A and B

uint64_t a_desc = make_desc(A_smem + k * MMA_K);

uint64_t b_desc = make_desc(B_smem + k * MMA_K);

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, a_desc, b_desc, i_desc, 1);

}

// use the same mbarrier to track the completion of tcgen05.mma operations

asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::1.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.b64 [%0];"

:: "r"(mbar_addr) : "memory");

}

// wait for MMA to finish

mbarrier_wait(mbar_addr, phase);

phase ^= 1; // flip the phase

}

Let’s go back to the shared memory descriptor. I find the PTX doc for this is rather lacking and confusing. You find these 2 foreign concepts, together with their respective sections in the PTX doc (we are not using any swizzling here, and both A and B are K-major, so look for those sections).

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Leading dimension byte offset (LBO) | “the stride from the first column to the second column of the 8x2 tile in the 128-bit element type normalized matrix.” |

| Stride dimension byte offset (SBO) | “The offset from the first 8 rows to the next 8 rows.” |

What the hell are these!!! I went on a little adventure trying to understand these myterious terms. Pranjal’s Hopper tutorial went straight to 128-byte swizzling TMA, which meant the corresponding shared memory descriptors wouldn’t be relevant to our case (no swizzling).

- This assumes

tcgen05works somewhat similarly to howwgmmadoes (I don’t have prior experience with Hopper, and still haven’t checked carefully if this assumption holds). - I could have gone with 128B swizzling directly (so that Pranjal’s code could be applicable to my case), but I thought it was more important that I understood the required input layouts and how to encode them in shared memory descriptors regardless of the swizzling type used.

I continued searching for other resources that could explain this. Surprisingly, Modular was the only one that explicitly discussed a key hidden concept - Core Matrices - in their 2nd blogpost of the Blackwell GEMM series.

In tcgen05.mma, there is an implicit unit of 8x16B (8 rows of 16 bytes each). Modular called it Core Matrix in the blogpost (which I guess came from Colfax Research’s WGMMA article), but it’s not mentioned anywhere in PTX doc. So I was (and still am) uncertain if it was the right term to call it. Anyway, in the LBO and SBO definitions above, “8x2 tile”, “128-bit element type”, and “8 rows” refer to this core matrix.

- 128-bit is equivalent to 16-byte.

- 8x2 tile and 8 rows clearly indicate the 8 rows of core matrix.

- 8x2 tile corresponds to 32-byte width, which is the same as the MMA shape’s K-dim (

k16for BF16). Coincidence? I think not. - The shape/size of core matrix is also the same as

ldmatrixsize.

That made things much clearer now, or so I thought. At this point, my mental picture of LBO and SBO looked like this.

My initial understanding of LBO and SBO. Each smaller tile is a core matrix within the larger threadblock tile in shared memory.

Given a BF16 tile of [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K], we divided it into sub-tiles of size [8, 8]. LBO, being “the stride from the first column to the second column of the 8x2 tile”, was simply 16 bytes. SBO, being “the offset from the first 8 rows to the next 8 rows”, was 8 x BLOCK_K x sizeof(nv_bfloat16) because that was how much to go through all 8 rows of the [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K] tile. I implemented it in code.

auto make_desc = [](int addr) -> uint64_t {

const int LBO = 16;

const int SBO = 8 * BLOCK_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

return desc_encode(addr) | (desc_encode(LBO) << 16ULL) | (desc_encode(SBO) << 32ULL) | (1ULL << 46ULL);

};

However, the result was wrong! I dug deeper into the PTX doc and found mentions of Canonical layouts. One of them looked like this.

- By this time I had actually implemented the epilogue so that I could do correctness check on the final result. But for the sake of the blogpost’s flow, let’s delay the epilogue to later.

Canonical layout for K-major, no swizzling, and TF32 dtype. Source: NVIDIA PTX doc.

It was not clear what the colors, numbers, and grid represented. Which one was the physical layout, which one was the logical layout? It was mentioned that LBO=64*sizeof(tf32) and SBO=32*sizeof(tf32) for the diagram above, but how would I calculate this for my case of [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K] tile? Perhaps it was my stubbornness not learning CuTe’s layout algebra (and their way of illustrating layouts) that prevented me from understanding this diagram.

I went back to the Modular blogpost, and noticed this one particular sentence.

where each column of core matrices (8x1) needs to be contiguous in shared memory.

This was the Aha moment for me! Each of the 8x16B tile must be contiguous, which spans 128B. An important consequence is that we need to change the layout of A and B in shared memory.

Updated shared memory layout for A and B. Notice each 8x16B tile now spans a contiguous chunk of memory.

Since now we have multiple [BLOCK_M, 16B] slices, we can’t issue a single 2D TMA directly. A simple solution is to issue 2D TMA multiple times (BLOCK_K / 16B) to be exact. This is the approach used in the Modular blogpost.

// host: encode 2D tensor map for A and B

// (only A is shown below)

constexpr uint32_t rank = 2;

uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {8, M}; // 8 is eight BF16 elements = 16 bytes

uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)}; // in bytes

uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {8, BLOCK_M};

// device: issue multiple 2D TMAs

for (int k = 0; k < BLOCK_K / 8; k++) {

// select K global offset

const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K + k * 8;

// A_smem and B_smem are raw shared address, with type int.

// each TMA copies [BLOCK_M, 16B] of A -> (BLOCK_M * 16) bytes.

// we index into the destination appropriately.

tma_2d_gmem2smem(A_smem + k * BLOCK_M * 16, &A_tmap, off_k, off_m, mbar_addr);

tma_2d_gmem2smem(B_smem + k * BLOCK_N * 16, &B_tmap, off_k, off_n, mbar_addr);

}

Another way to do this is to use 3D TMA.

Tile shape (boxDim) | Global stride | Comment |

|---|---|---|

[BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K] | [K, 1] | Original layout of threadblock tile in global memory. |

[BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K / 8, 8] | [K, 8, 1] | “Unflatten” the last dim. |

[BLOCK_K / 8, BLOCK_M, 8] | [8, K, 1] | Swap the first 2 dims. |

Notice that in TMA, it’s implied that the shared memory destination has the natural contiguous layout of the given shape (we don’t specify shared memory stride anywhere). Hence, [BLOCK_K / 8, BLOCK_M, 8] is the exact layout we need: contiguous tiles of [BLOCK_M, 8]. You realize by now that globalStrides in a tensor map doesn’t need to be monotically increasing.

// host: encode 3D tensor map for A and B

// (only A is shown below)

// everything is in reverse order of what is shown in the table above.

constexpr uint32_t rank = 3;

uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {8, M, K / 8};

uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16), 16}; // in bytes

uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {8, BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K / 8};

// device: issue a single 3D TMA

const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K;

tma_3d_gmem2smem(A_smem, &A_tmap, 0, off_m, off_k / 8, mbar_addr);

tma_3d_gmem2smem(B_smem, &B_tmap, 0, off_n, off_k / 8, mbar_addr);

Issuing 3D TMA is not much different from doing so for 2D TMA. You can consult the PTX doc for more details.

Going back to the mysterious LBO and SBO, we have the much needed clarity now.

My updated interpretation of LBO and SBO. LBO is used to traverse to the next slice / column, while SBO is used to select the next 8x16B tile within a slice.

Remember that MMA_K is always 32 bytes, which requires 2 slices of 16-byte width. Hence, each MMA instruction needs to know where to get the data from the two slices (called “columns” in various texts). MMA_M can be smaller than BLOCK_M, though we always set BLOCK_M = MMA_M = 128 for simplicity.

We have the complete code for issuing tcgen05.mma.

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

auto make_desc = [](int addr, int height) -> uint64_t {

const int LBO = height * 16;

const int SBO = 8 * 16;

return desc_encode(addr) | (desc_encode(LBO) << 16ULL) | (desc_encode(SBO) << 32ULL) | (1ULL << 46ULL);

};

// manually unroll 1st iteration to disable accumulation

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, make_desc(A_smem, BLOCK_M), make_desc(B_smem, BLOCK_N), i_desc, iter_k);

for (int k = 1; k < BLOCK_K / MMA_K; k++) {

// select the [BLOCK_M, 32B] tile for MMA,

// which consists of two [BLOCK_M, 16B] tiles.

uint64_t a_desc = make_desc(A_smem + k * BLOCK_M * 32, BLOCK_M);

uint64_t b_desc = make_desc(B_smem + k * BLOCK_N * 32, BLOCK_N);

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, a_desc, b_desc, i_desc, 1);

}

asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::1.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.b64 [%0];"

:: "r"(mbar_addr) : "memory");

}

The final piece to complete our basic kernel is writing the epilogue using tcgen05.ld. One particular thing about Tensor memory is that each warp only has partial access to it. Using MMA_M=128 and .cta_group::1, our kernel corresponds to Layout D.

tcgen05 Data path Layout D. Source: NVIDIA PTX doc.

This means that our kernel requires at least 4 warps, even though we only need 1 warp to issue TMA and MMA. For each warp, there are a few tcgen05.ld options for us to choose from, but I went with the simplest one - .32x32b.

tcgen05 Matrix fragment for .32x32b. Source: NVIDIA PTX doc.

Using the .x8 multiplier, each thread loads 8 consecutive FP32 accumulator values, which are then cast and packed into 8 BF16 values, or 16 bytes. This allows us using 16-byte stores, though it’s still uncoalesced.

// this is required before tcgen05.ld and after tcgen05.mma

// to form correct execution ordering.

// see https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/parallel-thread-execution/#tcgen05-memory-consistency-model-canonical-sync-patterns-non-pipelined-diff-thread

asm volatile("tcgen05.fence::after_thread_sync;");

// load 8 columns from tmem at a time -> store 16 bytes per thread to smem

for (int n = 0; n < BLOCK_N / 8; n++) {

// https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/parallel-thread-execution/#tcgen05-data-path-layout-d

// Layout D

float tmp[8];

const int row = warp_id * 32;

const int col = n * 8;

const int addr = taddr + (row << 16) + col; // 16 MSBs encode row, 16 LSBs encode column.

asm volatile("tcgen05.ld.sync.aligned.32x32b.x8.b32 {%0, %1, %2, %3, %4, %5, %6, %7}, [%8];"

: "=f"(tmp[0]), "=f"(tmp[1]), "=f"(tmp[2]), "=f"(tmp[3]),

"=f"(tmp[4]), "=f"(tmp[5]), "=f"(tmp[6]), "=f"(tmp[7])

: "r"(addr));

// wait for the completion of tcgen05.ld

asm volatile("tcgen05.wait::ld.sync.aligned;");

// cast and pack

nv_bfloat162 out[4];

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++)

out[i] = __float22bfloat162_rn({tmp[i * 2], tmp[i * 2 + 1]});

// 16-byte per thread write (uncoalesced)

nv_bfloat16 *out_ptr = C_ptr + (off_m + tid) * N + (off_n + n * 8);

reinterpret_cast<int4 *>(out_ptr)[0] = reinterpret_cast<int4 *>(out)[0];

}

// ensure all threads finish reading data from tmem before deallocation

__syncthreads();

if (warp_id == 0)

asm volatile("tcgen05.dealloc.cta_group::1.sync.aligned.b32 %0, %1;" :: "r"(taddr), "r"(BLOCK_N));

This completes our first version of tcgen05 kernel! You can find the full code at matmul_v1.cu.

- I left out one minor instruction - elect.sync. Instead of statically appointing the first thread to issue TMA and MMA (i.e.

if (tid == 0)), we can use this instruction to let the GPU decide which thread to be “elected” instead. I haven’t deeply investigated if this brings any noticeable speedups, and if it does, what would explain it. I saw its usage in DeepGEMM, hence it’s probably a good idea to follow. - It’s also possible to use TMA for storing C to global memory as well. It was in fact how I did it initially. However, I found that doing a simple global store from registers was faster.

Running some benchmarks for M=N=K=4096.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v1a (basic tcgen05 + 2D 16B TMA) | 254.62 |

| v1b (3D 16B TMA) | 252.81 |

Oof. We are getting less than 20% of CuBLAS speed (on Modal, the best TFLOPS I can get from CuBLAS is ~1700 with a larger problem shape, so ~1500 TFLOPS is not bad). What’s more interesting is that using 3D TMA (with one issuance) is slower than using 2D TMA (with multiple issuances). It indicates that not all layouts can get good performance out of the TMA engine.

Even though we haven’t gotten a good speed yet, I’m quite happy at this point as we have successfully understood many new pieces of tcgen05 and how they link together.

| Concept | Key points |

|---|---|

mbarrier | Initialization and its semantics to synchronize TMA and tcgen05.mma. |

| Tensor memory | Allocation and deallocation, encode and select Tensor memory address. |

| TMA | Encode tensor map on host, issue TMA on device using cp.async.bulk.tensor, synchronize with mbarrier. |

| MMA | Prepare correct input layouts and their shared memory descriptors, issue tcgen05.mma, synchronize with mbarrier. |

| Epilogue | Retrieve data out of Tensor memory. |

128-byte global load and swizzling

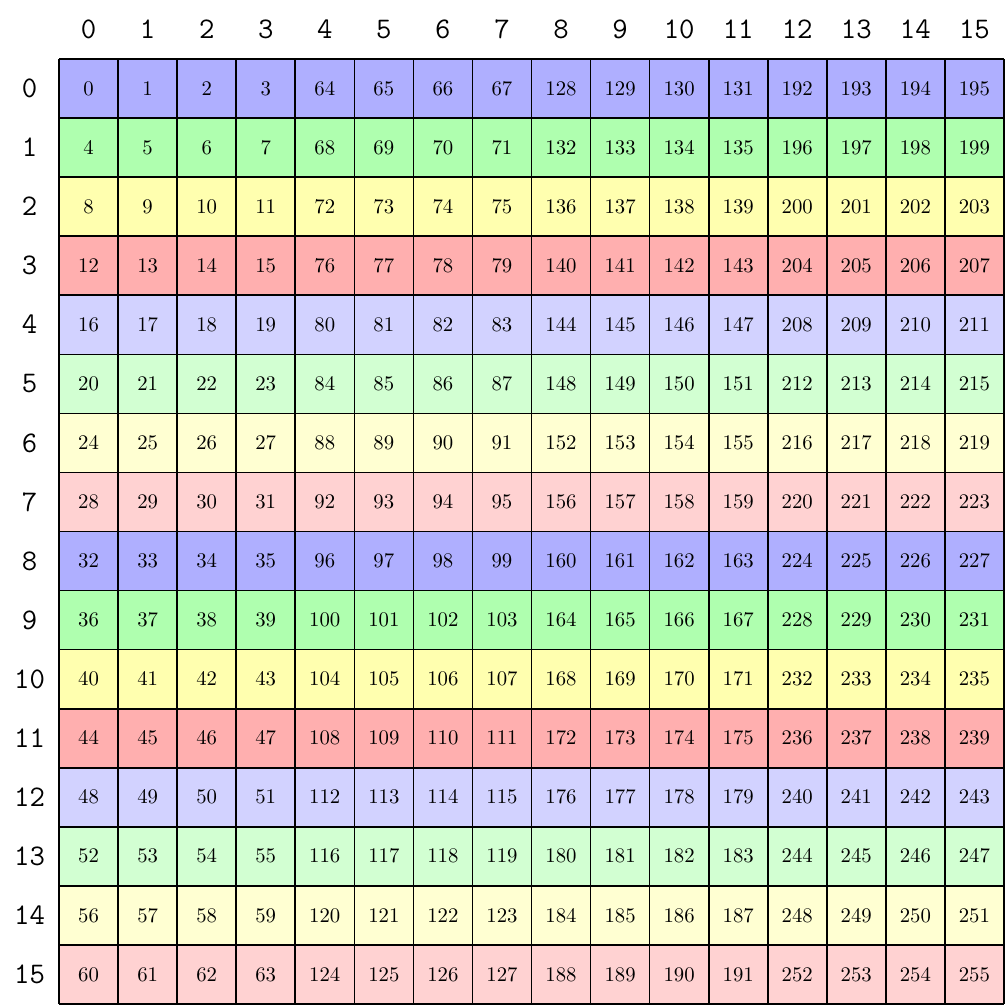

I roughly know that we should use 128-byte swizzling, the largest supported swizzling size by the TMA, so let’s look into it next. I won’t cover swizzling extensively here, you should refer to other articles for a more detailed explanation.

Swizzling is a technique to avoid shared memory bank conflicts by distributing the data (being loaded by a particular access pattern) across all 32 memory banks. I built a Bank Conflict Visualizer to illustrate this before. By default, it’s showing the access pattern of ldmatrix (8x16B) for a BF16 case, which suffers from bank conflicts. Swizzling typically involves XOR-ing the column indices with their row indices so that elements within the same row are permuted differently across rows.

Swizzling in TMA is in the granularity of 16 bytes. Different swizzling patterns specify the size of data to be swizzled. For example, CU_TENSOR_MAP_SWIZZLE_128B means in a chunk of 128 bytes, we have eight 16-byte units. These eight units are permuted according to its row index. This can be visualized like below.

- Technically the visualization is not quite correct as there is a constraint on the row size for each swizzling type.

Some swizzling patterns supported by TMA.

To reproduce the swizzling patterns above with my interactive visualizer, you can set:

- BLOCK_M and BLOCK_N to 8

- Element size to 16 bytes

- Access group height to 8

- Access group width to 1

and use the swizzle function as shown in the picture.

Before modifying the code, we need to understand how tcgen05.mma understands swizzled shared memory. Bit 61-63 of the shared memory descriptor specify the swizzling mode, but we are still not sure how the shared memory layout should look like. Backtracking to the Canonical layouts section, we see this table.

| Swizzling mode | Canonical layout without swizzling | Swizzling on the previous column |

|---|---|---|

| None | ((8,m),(16B,2k)):((1x16B,SBO),(1,LBO)) | Swizzle<0, 4, 3> |

| 32B | ((8,m),(16B,2k)):((2x16B,SBO),(1,16B)) | Swizzle<1, 4, 3> |

| 64B | ((8,m),(16B,2k)):((4x16B,SBO),(1,16B)) | Swizzle<2, 4, 3> |

| 128B | ((8,m),(16B,2k)):((8x16B,SBO),(1,16B)) | Swizzle<3, 4, 3> |

My knowledge of CuTe layouts is pretty limited, but let’s attempt to unwrap some of these.

- I have replaced

Twith16B, which I believe makes things clearer. - Looking at the None swizzling case, which is our v1 kernel, we can see it has shape

((8,m),(16B,2k))(everything before the colon) and stride((1x16B,SBO),(1,LBO))(everything after the colon). ((8,m),(16B,2k))is a composite tuple, which can be understood as a large[8*m, 16B*2k]tile with multiple smaller[8, 16B]tiles inside. The[8, 16B]tiles are exactly the core matrices!- Notice the stride of dim

8, which is the distance to go to the next row.SWIZZLE_NONEhas stride16B, corresponding to our previously knowledge that each8x16Btile must be contiguous in memory. - For

SWIZZLE_32B, the stride becomes2x16B, which heavily implies there is a 32-byte width somewhere in the physical layout. Similar observations can be made forSWIZZLE_64BandSWIZZLE_128B!

Again, I don’t understand 90% of these layout algebra, and I probably use the wrong terms and language to describe these. But we roughly know that using SWIZZLE_32B / SWIZZLE_64B / SWIZZLE_128B will result in something being 32-byte / 64-byte / 128-byte wide. This is most likely the width of the 2D TMA tile, as doing SWIZZLE_128B requires having the inner-most dim of TMA to be 128 bytes.

My understanding of the required shared memory layout for tcgen05 when swizzling is used. Both before and after swizzling are shown for ease of visualization.

To put it into words, tcgen05 without swizzling requires each 8x16B tile to be a contiguous chunk, while 32B swizzling requires each 8x32B tile to be a contiguous chunk, where each chunk has its 16-byte units swizzled internally. Similar logic can be applied for 64B swizzling and 128B swizzling. In other words, for 128B swizzling, we are looking at 8x128B tiles.

- I don’t visualize 128B swizzling in the diagram above as it would be too tedious and take up too much space, but I hope you can visualize it in your head.

The changes in our code are quite straightforward. When encoding the tensor map, we set the two inner dims to 8x128B instead of 8x16B, and set swizzling to SWIZZLE_128B.

// for 2D TMA

constexpr uint32_t rank = 2;

- uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {8, M};

- uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)}; // in bytes

- uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {8, BLOCK_M};

+ uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {64, M};

+ uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)}; // in bytes, unchanged

+ uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {64, BLOCK_M};

// for 3D TMA

constexpr uint32_t rank = 3;

- uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {8, M, K/8};

- uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16), 16}; // in bytes

- uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {8, BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K/8};

+ uint64_t globalDim[rank] = {64, M, K/64};

+ uint64_t globalStrides[rank-1] = {K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16), 128}; // in bytes

+ uint32_t boxDim[rank] = {64, BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K/64};

// for both 2D TMA and 3D TMA

auto err = cuTensorMapEncodeTiled(

...

- CUtensorMapSwizzle::CU_TENSOR_MAP_SWIZZLE_NONE,

+ CUtensorMapSwizzle::CU_TENSOR_MAP_SWIZZLE_128B,

...

);

Inside the kernel, we make small adjustments to TMA issuance. The layout is already encoded inside the tensor map, so we only need to recompute the correct offsets and loop iterations count.

// issue TMA

if constexpr (TMAP_3D) {

const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K;

- tma_3d_gmem2smem(A_smem, &A_tmap, 0, off_m, off_k / 8, mbar_addr);

- tma_3d_gmem2smem(B_smem, &B_tmap, 0, off_n, off_k / 8, mbar_addr);

+ tma_3d_gmem2smem(A_smem, &A_tmap, 0, off_m, off_k / 64, mbar_addr);

+ tma_3d_gmem2smem(B_smem, &B_tmap, 0, off_n, off_k / 64, mbar_addr);

} else {

- for (int k = 0; k < BLOCK_K / 8; k++) {

- const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K + k * 8;

- tma_2d_gmem2smem(A_smem + k * BLOCK_M * 16, &A_tmap, off_k, off_m, mbar_addr);

- tma_2d_gmem2smem(B_smem + k * BLOCK_N * 16, &B_tmap, off_k, off_n, mbar_addr);

- }

+ for (int k = 0; k < BLOCK_K / 64; k++) {

+ const int off_k = iter_k * BLOCK_K + k * 64;

+ tma_2d_gmem2smem(A_smem + k * BLOCK_M * 128, &A_tmap, off_k, off_m, mbar_addr);

+ tma_2d_gmem2smem(B_smem + k * BLOCK_N * 128, &B_tmap, off_k, off_n, mbar_addr);

+ }

}

For MMA, we need to make 2 key changes. First is the shared memory descriptor. (2ULL << 61ULL) encodes 128-byte swizzling. We don’t need to encode LBO as PTX assumes it to be 1 (though I don’t even try to interpret what LBO means in the swizzling case LOL).

auto make_desc = [](int addr) -> uint64_t {

const int SBO = 8 * 128; // size of the 8x128B tile

return desc_encode(addr) | (desc_encode(SBO) << 32ULL) | (1ULL << 46ULL) | (2ULL << 61ULL);

};

The second change, which requires a bit more thoughts, is updating how to select the right shared memory address. Remember that our data is swizzled now. Consider the case of 64B swizzling (because I don’t have enough real estate to draw 128B swizzling).

Visualization of MMA tiles in shared memory when 64-byte swizzling is used. BLOCK_M and MMA_M should be 128 (or 16 units of 8x16B), but they are set to 32 (or 4 units of 8x16B) for a compact diagram.

The physical layout of each MMA tile looks rather complicated. If we ignore the “1st address” and “2nd address” arrows, it’s quite perplexing how to correctly encode the shared memory descriptors for the MMA tiles. Recall that we can only supply 1 shared memory address to the descriptor. Perhaps the sane thing is to just look at the first row, and hope the hardware is wired to do the correct thing. That is where “1st address” and “2nd address” come from, which turn out to be the right way to interpret it!

For the actual code, we have 2 nested loops now: the first one iterates [BLOCK_M, 128B] (TMA tile?) over [BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K] (threadblock tile), and the second one iterates [BLOCK_M, 32B] (MMA tile) over [BLOCK_M, 128B].

// manually unroll 1st iteration to disable accumulation

{

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, make_desc(A_smem), make_desc(B_smem), i_desc, iter_k);

for (int k2 = 1; k2 < 64 / MMA_K; k2++) {

uint64_t a_desc = make_desc(A_smem + k2 * 32);

uint64_t b_desc = make_desc(B_smem + k2 * 32);

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, a_desc, b_desc, i_desc, 1);

}

}

// k1 selects the (BLOCK_M, 64) tile.

// k2 selects the (BLOCK_M, 16) tile, whose rows are swizzled.

for (int k1 = 1; k1 < BLOCK_K / 64; k1++)

for (int k2 = 0; k2 < 64 / MMA_K; k2++) {

uint64_t a_desc = make_desc(A_smem + k1 * BLOCK_M * 128 + k2 * 32);

uint64_t b_desc = make_desc(B_smem + k1 * BLOCK_N * 128 + k2 * 32);

tcgen05_mma_f16(taddr, a_desc, b_desc, i_desc, 1);

}

asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::1.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.b64 [%0];"

:: "r"(mbar_addr) : "memory");

That’s it to support 128B swizzling - matmul_v2.cu. Running the benchmarks again.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v1a (basic tcgen05 + 2D 16B TMA) | 254.62 |

| v1b (3D 16B TMA) | 252.81 |

| v2a (2D 128B TMA) | 681.20 |

| v2b (3D 128B TMA) | 695.43 |

A huge speed boost! 2.7x faster compared to v1, reaching 46% of CuBLAS without pipelining. We can move on from this kernel, but I have two small remarks.

Do we need to understand swizzling? Notice in our code, we are not manually computing swizzling anywhere. We only set CU_TENSOR_MAP_SWIZZLE_128B in the tensor map encoding and set bits 61-63 to 2 for the shared memory descriptor. In other words, even if swizzling is implemented differently in the hardware, our code remains the same and stays correct, as long as TMA and tcgen05.mma agree on the same swizzling implementation.

- Personally, I feel 128B swizzling is more about using a wider tile (from 16 bytes to 128 bytes) rather than about swizzling. If we want to use 128B-wide tiles with

tcgen05.mma, we have to use 128B swizzling.

Is the speedup due to removing bank conflicts? Swizzling is known as a technique to avoid bank conflicts. But did we face bank conflicts in our first kernel? Recall that each 8x16B tile is contiguous in memory for the first kernel, which spans exactly over 32 banks! There should be no bank conflicts even in our first kernel.

- This analysis assumes the shared memory access pattern of

tcgen05.mmais to load one8x16Btile at a time. It’s well known thatldmatrix.x4does this (though it’s not documented in PTX), but there is no guarantee thattcgen05.mmafollows the same pattern. For example, folks writing matmuls for AMD MI300 know that the GPU uses a different access pattern (reads and writes have different patterns!). We can verify this with ncu though, but Modal doesn’t provide ncu access. - A possible reason for the speedup that I can think of is simply faster global memory loads when the innermost dim of TMA is larger. In the case of 3D TMA, the overall shape is the same (

[BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K]) between v1 and v2 kernels. This reinforces the idea that the TMA engine works better with certain access patterns than some others. It would be an interesting project to do TMA microbenchmarking (maybe some have already done it but I’m not aware of). Again, this reason can be verified with ncu.

Pipelining

The natural next step is to implement pipelining. We are doing it the “Ampere-style”. Pipelining with N stages means we always have N stages of global->shared loads in flight, each owning a separate shared memory buffer. At the high level, it looks like this.

template <int BLOCK_N, int BLOCK_K, int NUM_STAGES>

__global__

__launch_bounds__(TB_SIZE)

void kernel(

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap A_tmap,

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap B_tmap,

nv_bfloat16 *C_ptr,

int M, int N, int K

) {

...

// use lambda for convenience.

auto load = [&](int iter_k) {

... // issue TMA here

};

auto compute = [&](int iter_k) {

... // issue tcgen05.mma here

};

// prefetch N-1 stages

for (int stage = 0; stage < NUM_STAGES; stage++)

load(stage);

// main loop, iterate along K dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < K / BLOCK_K; iter_k++) {

// prefetch the next stage -> N stages in flight now

load(iter_k + NUM_STAGES - 1);

// wait for the current load stage to finish

...

// N-1 load stages in flight now,

// but we are also doing 1 compute stage.

compute(iter_k);

// wait for the current compute stage to finish

// so that the buffer is freed up for the next prefetch.

...

}

}

We need a way to wait for a specific TMA load stage. The solution is simple: use 1 mbarrier for each TMA stage. Most of the code changes are not too interesting, you can refer to matmul_v3.cu.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v2b (3D 128B TMA) | 695.43 |

| v3 (pipelining) | 939.61 |

It’s a good speedup (35%), but not as drastic as the previous one.

Warp specialization

I have came across the Warp specialization concept a few times before, first introduced by Cutlass for writing performant Hopper GEMMs. The idea is simple: since we only need 1 thread to issue TMA and MMA, let’s dedicate 1 warp for each task! Each warp runs their own mainloop to avoid checking if (warp_id == 0) inside the loop.

const int num_iters = K / BLOCK_K;

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

// TMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

}

else if (warp_id == 1 && elect_sync()) {

// MMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

}

For Blackwell (and also Hopper), since the Tensor cores operate asynchronously with respect to the programmer’s threads, we can issue multiple tcgen05.mma without waiting for them to finish before moving on to the next stage. Care is still required to ensure TMA only starts data copy when MMA has finished using the buffer of the current stage.

4-stage pipelining in Ampere (top) and Blackwell with warp specialization (bottom).

To be able to wait for different MMA stages independently, we use multiple mbarrier objects, just like how we wait for each TMA stage previously.

// set up mbarrier

// we have NUM_STAGES mbars for TMA

// NUM_STAGES mbars for MMA

#pragma nv_diag_suppress static_var_with_dynamic_init

__shared__ uint64_t mbars[NUM_STAGES * 2];

const int tma_mbar_addr = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(mbars));

const int mma_mbar_addr = tma_mbar_addr + NUM_STAGES * 8;

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_STAGES; i++) {

// MMA warp checks the completion of TMA using tma_mbar

// there is only 1 thread issuing TMA, hence init mbar with 1.

mbarrier_init(tma_mbar_addr + i * 8, 1);

// TMA warp checks the completion of MMA using mma_mbar

// there is only 1 thread issuing MMA, hence init mbar with 1.

mbarrier_init(mma_mbar_addr + i * 8, 1);

}

asm volatile("fence.mbarrier_init.release.cluster;"); // visible to async proxy

}

In the actual code for TMA and MMA warps, we select the correct mbarrier for waiting and signalling. It’s not too interesting so you can check them in the full code later.

- Perhaps one thing to pay attention to is that in the beginning, TMA should NOT wait for MMA. This is because at

phase = 0, the shared buffer is available for TMA (to start copying data). To handle this, simply flip the phase that TMA warp uses to check for MMA completion.

// inside the code for TMA warp

// wait for MMA

const int stage_id = iter_k % NUM_STAGES;

mbarrier_wait(mma_mbar_addr + stage_id * 8, phase ^ 1);

- Waiting for the wrong phase can lead to deadlock, as both TMA and MMA wait for each other.

- This was how I first implemented it, following DeepGEMM. But in retrospect, a simpler approach would be to let TMA and MMA warps have their own variables to track the phase parity. Then in TMA warp, we can initialize

mma_phase = 1, and in MMA warp,tma_phase = 0. This would also signal clearer intentions to the readers, asphasealone may refer to different things at different parts of the kernel.

For the epilogue, initially I used __syncthreads() to wait for TMA and MMA warps to finish, before proceeding with the epilogue.

// warp specialization

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

// TMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

}

else if (warp_id == 1 && elect_sync()) {

// MMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

}

// wait for all warps to reach here

__syncthreads();

// epilogue code

...

However, I kept getting correctness issues. Upon closer inspection, I realized that __syncthreads() did not guarantee MMA had finished, but only that the last tcgen05.mma had been issued. To wait for the last MMA iteration correctly, we need to use an mbarrier. One idea is to do some calculations and figure out which mbarrier corresponds to the last MMA iteration (and also its current phase). A simpler idea is to use an extra mbarrier, and do a tcgen05.commit to this mbarrier after the main loop. I went with the second approach.

// set up mbarrier

// we have NUM_STAGES mbars for TMA

// NUM_STAGES mbars for MMA

// 1 mbar for mainloop

#pragma nv_diag_suppress static_var_with_dynamic_init

__shared__ uint64_t mbars[NUM_STAGES * 2 + 1];

const int tma_mbar_addr = static_cast<int>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(mbars));

const int mma_mbar_addr = tma_mbar_addr + NUM_STAGES * 8;

const int mainloop_mbar_addr = mma_mbar_addr + NUM_STAGES * 8;

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_STAGES; i++) {

mbarrier_init(tma_mbar_addr + i * 8, 1);

mbarrier_init(mma_mbar_addr + i * 8, 1);

}

// epilogue warps check for the completion of mainloop using mainloop_mbar

// there is only 1 thread issuing TMA, hence init mbar with 1.

mbarrier_init(mainloop_mbar_addr, 1);

asm volatile("fence.mbarrier_init.release.cluster;"); // visible to async proxy

}

// other initial kernel setup

...

// warp specialization

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

// TMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

}

else if (warp_id == 1 && elect_sync()) {

// MMA warp

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++)

...

// signal when tcgen05 finishes with the main loop

asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::1.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.b64 [%0];"

:: "r"(mainloop_mbar_addr) : "memory");

}

// wait for mainloop to finish

__syncthreads();

mbarrier_wait(mainloop_mbar_addr, 0); // implied using phase = 0

The __syncthreads() is optional, but my logic was that it would prevent the other 2 warps (that did not issue TMA and MMA) from doing unnecessary spinning on the mbarrier before the last tcgen05.mma was issued. I also thought it could be a safeguard to prevent warp divergence for the TMA and MMA warps, as the C++ program does not prevent non-elected threads from continuing execution (though nvcc and ptxas could have already put in the necessary safeguards, or maybe it’s part of the CUDA semantics that I don’t know about). Anyway, these are just my speculations, and I didn’t put in the efforts to investigate it.

matmul_v4.cu gains ~29% speedup! We are getting quite close to CuBLAS speed now.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v3 (pipelining) | 939.61 |

| v4 (warp specialization) | 1208.83 |

2-SM MMA

Another cool feature in Blackwell is that we can use Tensor cores across 2 threadblocks to cooperatively compute an MMA tile together. In terms of data organization, it looks like this.

Data organization in 2-SM MMA. A0, B0, C0 stay on CTA0, while A1, B1, C1 stay on CTA1.

Each CTA (a fancier term for threadblock) provides half of A tile and B tile, and also holds half of the outputs. MMA_M goes up to 256, double of that in the standard 1-SM MMA (BLOCK_M remains 128). MMA_N’s limit doesn’t change (up to 256), but now each CTA only needs to hold half of B tile. If I were to guess, it looks like the Tensor cores of each CTA still load its local A tile as usual (computing C0 doesn’t require touching A1, and vice versa), but it will load half of B tile in each CTA: one half from its local shared memory, and the other half from its Peer CTA’s shared memory (this is the proper terminology used in PTX doc).

- Interestingly, the diagram you see above is not found or hinted anywhere in the PTX doc, at least to my knowledge. But it’s explained in a few other places: 2nd blogpost of Modular’s Blackwell series and Colfax’s Blackwell article.

For 2 Streaming Processors (SMs) to work together, we need to launch the kernel with Threadblock clusters enabled.

__global__

__cluster_dims__(2, 1, 1)

__launch_bounds__(TB_SIZE)

void kernel(

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap A_tmap,

const __grid_constant__ CUtensorMap B_tmap,

nv_bfloat16 *C_ptr,

int M, int N, int K

) {

// CTA rank in a cluster

int cta_rank;

asm volatile("mov.b32 %0, %%cluster_ctarank;" : "=r"(cta_rank));

...

}

To determine the current block’s CTA rank, we can read the %cluster_ctarank register directly. However, at least from my experience with 2-CTA clusters, two consecutive threadblocks form a cluster. Hence, you probably can get away with cta_rank = blockIdx.x % 2. You can definitely launch a larger cluster with more CTAs, but I haven’t found a good reason to try. We only need 2 CTAs for 2-SM MMA.

In this 2-SM MMA kernel, only 1 CTA issues MMA. As a result, our synchronization structure looks like this.

Synchronization pattern in 2-SM MMA design. Only CTA0 issues MMA. TMA waiting for MMA via MMA mbarrier is not shown for brevity.

You can notice that TMAs on both CTAs report their completion progress to CTA0’s TMA mbarrier. This is done so that CTA0 MMA, which is responsible for issuing MMA for both CTAs, can wait the completion of both TMAs using only its own local mbarrier. To do this in code, we modify the instruction as follows.

// clear the cluster rank bit of shared memory address

// https://github.com/NVIDIA/cutlass/blob/v4.3.1/include/cute/arch/copy_sm100_tma.hpp#L113-L115

- const int mbar_addr = tma_mbar_addr + stage_id * 8;

+ const int mbar_addr = (tma_mbar_addr + stage_id * 8) & 0xFEFFFFFF; // this is on CTA0

// change to .shared::cluster

- asm volatile("mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx.release.cta.shared::cta.b64 _, [%0], %1;"

+ asm volatile("mbarrier.arrive.expect_tx.release.cta.shared::cluster.b64 _, [%0], %1;"

:: "r"(mbar_addr), "r"(A_size + B_size) : "memory");

- There is no major change in issuing TMAs, since each CTA still loads data to its own shared memory. We only update which

mbarrierto reports the progress to. For B, we only load half of B tile. - By right, we have to use the mapa instruction to map a local shared address to that in another CTA. However, I found the masking trick in Cutlass code, hence just use it directly.

If we follow the execution order of the kernel, it would be appropriate to discuss about the changes in MMA-issuing code now. But that deserves its own subsection, so let’s cover other details first. In the diagram above, MMA warp on CTA0 tells mainloop mbarriers in both CTAs to track its completion. This is called multicast i.e. send one thing to multiple destinations. Although it’s not shown in the diagram due to limited space, CTA0 MMA also multicasts its completion to MMA mbarriers on both CTAs.

- asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::1.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.b64 [%0];"

- :: "r"(mma_mbar_addr + stage_id * 8) : "memory");

+ constexpr int16_t cta_mask = (1 << 2) - 1; // 0b11 in binary

+ asm volatile("tcgen05.commit.cta_group::2.mbarrier::arrive::one.shared::cluster.multicast::cluster.b64 [%0], %1;"

+ :: "r"(mma_mbar_addr + stage_id * 8), "h"(cta_mask) : "memory");

- A natural follow up question: how does the instruction know the remote shared memory address? Fortunately, the PTX doc provides clarifications on this (look for the section about

.cta_group::2).

The mbarrier signal is multicast to the same offset as

mbarin the shared memory of each destination CTA.

- We know from our previous Cutlass trick (

& 0xFEFFFFFF) that there is a bit field in a shared memory address to indicate it’s pointing to a remote region. So it’s likely that the hardware will iterate through thecta_maskand set this bit field to obtain the remote address (or it just looks at some of the LSBs). - There is an important consequence from this: Objects layout in shared memory must be identical across cluster ranks. Even if we don’t use TMA

mbarrierin CTA1, we can’t repurpose this memory for something else, since it may change the layout of all other objects.

Let’s go back to the subtopic of issuing MMAs. The fact that we are using 2-SM MMA is encoded in the .cta_group::2 modifier. Hence, we only need to adjust the instruction and shared memory descriptors. Instruction descriptor now encodes a larger tile, using MMA_M = 256 and tunable MMA_N. For shared memory descriptors, it was confusing to me at first: since input data is distributed across 2 CTAs, how should I encode them correctly? Recall that a shared memory descriptor takes in exactly one address, and tcgen05.mma itself only accepts one descriptor for A and one for B. It’s impossible to specify 2 distributed half tiles of A and B.

- PTX doc is quite sparse on this topic (or I just haven’t found the right sections) - the expected shared memory layout of A and B, as well as how to encode or select them for MMA. This reminds me of my previous misadventure with LBO and SBO. I had different hypotheses: maybe B should be replicated across CTA ranks so that we can all of them (but then what’s the point right); perhaps we manually invoke MMA on a remote shared memory address (which is not possible because a shared memory descriptor only keeps 18 LSBs of the shared memory address). They were all wrong of course.

Luckily, I got some clarifications from firadeoclus in the GPU-MODE Discord. He confirms that we only need to use the local shared memory address, and the hardware will fetch the data from remote shared memory having the same offset. This is similar to our tcgen05.commit with multicast previously. It further reinforces the requirement that objects layout in shared memory should be the same across cluster ranks.

In the end, we don’t actually make much changes in the MMA issuing code, because we still use the local buffer for shared memory descriptors. Some other minor details that I can’t find a natural way to fit them in the story:

tcgen05instructions within a kernel MUST be with either.cta_group::1or.cta_group::2. So you must use.cta_group::2for othertcgen05instructions not mentioned above as well, such astcgen05.alloc.- The equivalence of

__syncthreads()for cluster scope is the pairbarrier.cluster.arrive.release.aligned-barrier.cluster.wait.acquire.aligned. This should be used aftermbarrierand Tensor memory initialization, and before Tensor memory deallocation. (I didn’t actually use cluster barrier in this kernel for Tensor memory deallocation, and the correctness check passed, but it definitely introduced a race condition.) - Looking at the Data organization diagram at the start of this section, you can see that the CTA pair of a cluster is arranged along the M dim. This means that we have to adjust our block ID mapping. Note that this is not the only possible way.

// bid runs along N-mode first

- const int bid_m = bid / grid_n;

- const int bid_n = bid % grid_n;

// bid must run along M-mode first so that .cta_group::2 works correctly

+ constexpr int GROUP_M = 2;

+ const int bid_m = bid / (grid_n * GROUP_M) * GROUP_M + (bid % GROUP_M);

+ const int bid_n = (bid / GROUP_M) % grid_n;

You can check out matmul_v5. To be honest, the 8% speedup is rather disappointing.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v4 (warp specialization) | 1208.83 |

| v5 (2-SM MMA) | 1302.29 |

Persistent kernel (with static scheduling)

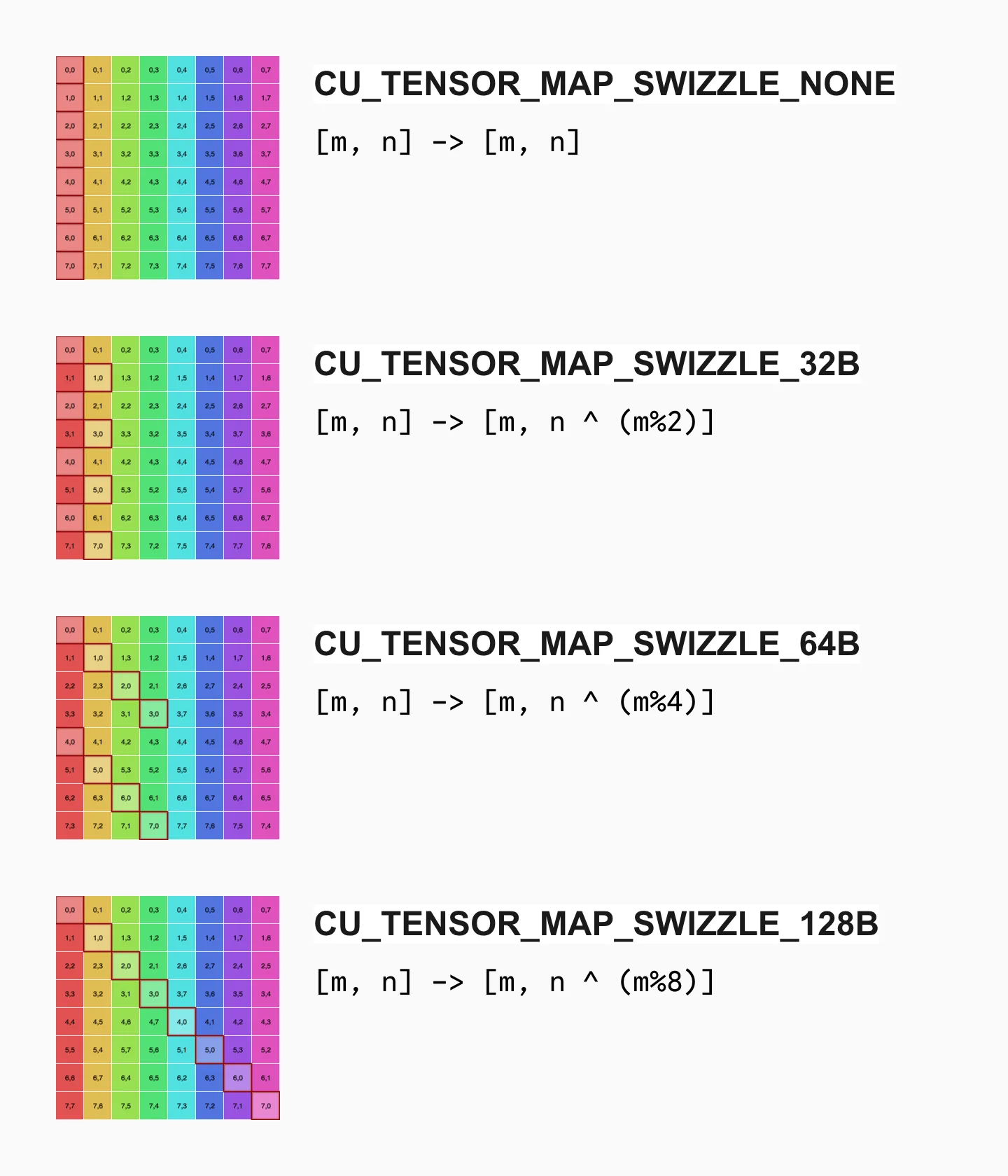

Up to this point, we have been optimizing the kernel blindly: we don’t do any profiling nor collect any metrics to identify bottlenecks to be resolved. It’s time we spend some efforts to profile the current kernel. Unfortunately, Modal doesn’t provide ncu access. But we have another trick up our sleeve: Intra-kernel profiling.

I wrote about this technique before that I used in the AMD Distributed competition. The idea is simple: read a clock register to record the starting and ending time of various events in the kernel, and format the data into a Chrome trace for visualization with UI Perfetto. The current blogpost is getting quite long and I don’t want to spend more words on this, so you can refer to profiler.h and matmul_v5.cu for the usage within the kernel, and main.py#L45 for host-side export.

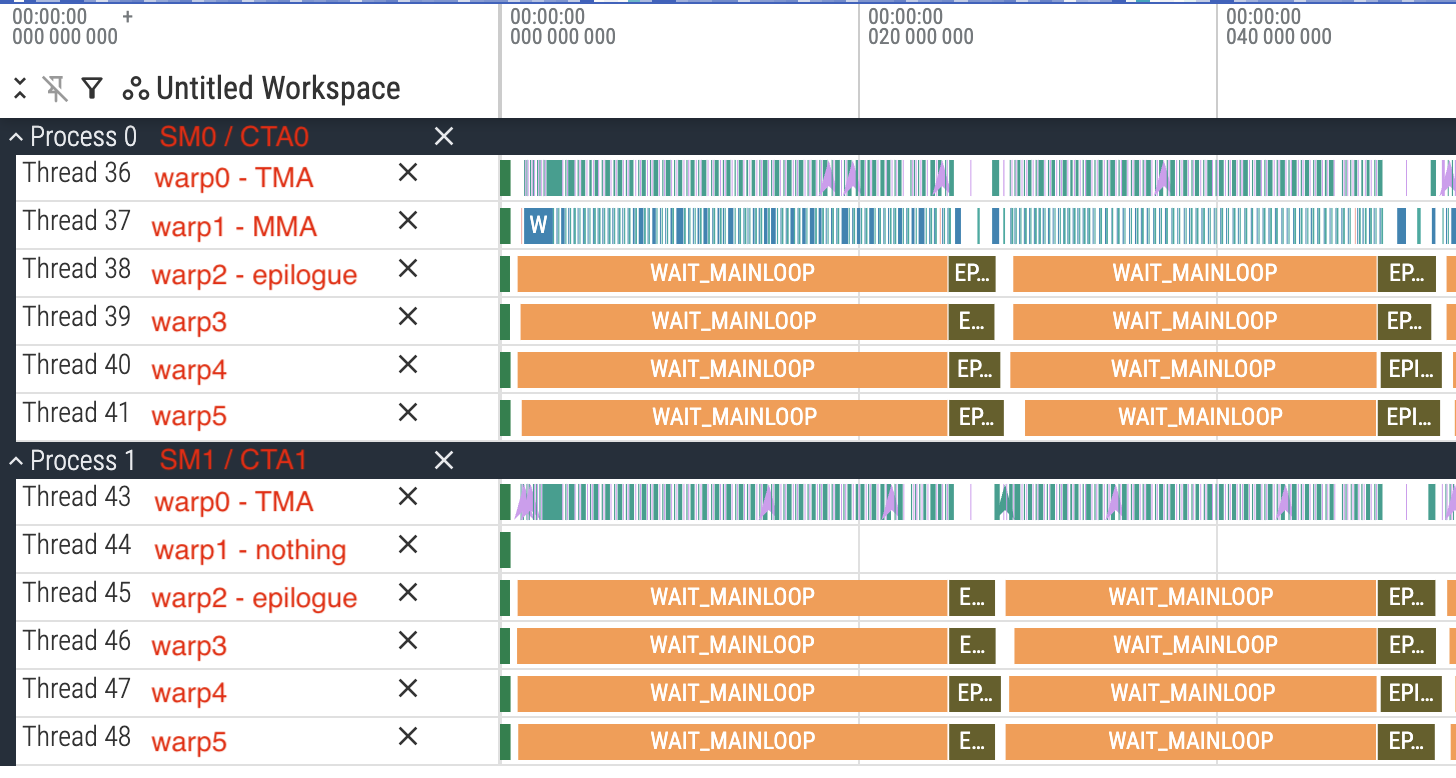

We obtain this Chrome trace for the 2-SM, warp specialization kernel.

Intra-kernel profile of kernel v5. Source: profile_v5.json.gz.

- You can download the Chrome trace using the link in the caption, and use https://ui.perfetto.dev/ to interact with it.

It’s quite obvious that the epilogue and the initial setup in the new threadblock are taking a considerable amount of kernel time, blocking the utilization of Tensor cores i.e. Tensor cores are idle during epilogue execution. The typical solution to this is Persistent kernel: we launch exactly 148 threadblocks (the number of SMs on Modal B200), and each threadblock will handle multiple output tiles sequentially, instead of having 1 threadblock for 1 output tile. The benefits are:

- One-time per-SM setup during the whole kernel’s duration, instead of having one setup per output tile.

- Overlap epilogue with TMA and MMA: while the epilogue warps are doing tmem->rmem, dtype cast, and rmem->gmem, TMA and MMA warps can continue working on the next output tile.

As always, we will use mbarrier to coordinate the warps properly. Before proceeding, let’s revisit our design of TMA<->MMA synchronization. We use 2 sets of mbarrier to signal each direction about ownership status of the shared buffers. In some sense, this is a circular buffer, or circular queue, where TMA puts fresh data into the queue, while MMA consumes it and frees up the resources after use.

We can extend this idea to our current mainloop->epilogue synchronization. Tensor memory is the buffer of concern now: mainloop is a producer, and epilogue is the consumer. It might be possible to get away without double-buffering Tensor memory (MMA for the next output tile waits for epilogue of the previous tile), but considering that we have plenty of Tensor memory (512 columns, while BLOCK_N can only go up to 256), I decide to go with double-buffering for Tensor memory anyway.

- Technically MMA warp is the producer here, but I prefer to call it “mainloop” instead because (1) this producer-consumer pair operate at a different frequency (per output tile instead of per input tile), and (2) I want to make a clear distinction of our two producer-consumer pairs.

Our high-level design looks like this.

if (warp_id == 0 && elect_sync()) {

// TMA warp

// iterate over output tiles

for (int this_bid = bid; this_bid < num_tiles; this_bid += num_bids) {

// mainloop: iterate along K-dim

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++) {

// wait for MMA of the current shared buffer

...

// issue TMA (producer for TMA<->MMA pair)

...

// signal TMA done

...

}

}

}

else if (cta_rank == 0 && warp_id == 1 && elect_sync()) {

// MMA warp (CTA0 only)

// iterate over output tiles

for (int this_bid = bid; this_bid < num_tiles; this_bid += num_bids) {

// wait for epilogue of the current tmem buffer

...

// mainloop: iterate along K-dim

// (producer for mainloop<->epilogue pair)

for (int iter_k = 0; iter_k < num_iters; iter_k++) {

// wait for TMA of the current shared buffer

...

// issue MMA (consumer of the TMA<->MMA pair)

...

// signal MMA done

...

}

// signal mainloop done

...

}

}

else if (warp_id >= 2) {

// epilogue warps

// iterate over output tiles

for (int this_bid = bid; this_bid < num_tiles; this_bid += num_bids) {

// wait for mainloop of the current tmem buffer

...

// perform epilogue (consumer of the mainloop<->epilogue pair)

...

// signal epilogue done

...

}

}

- There are 2 producer-consumer pairs: TMA<->MMA, and mainloop<->epilogue. The synchronization mechanism is the same i.e.

mbarrier, with different types of buffers for data passing (shared memory vs tensor memory). - Due to the added complexity (MMA warp needs to juggle between both TMA<->MMA pair and mainloop<->epilogue pair!), the details can be quite tricky to get right e.g. we can’t do

stage_id = iter_k % NUM_STAGESto select the shared memory buffer in the mainloop anymore since TMA and MMA now persist across output tiles. Do pay attention to them. - Notice that we have epilogue-specialized warps now, instead of reusing the TMA and MMA warps for epilogue. This is necessary because we need epilogue to operate independently from TMA and MMA. It means that we have 6 warps in total: 1 for TMA, 1 for MMA, and 4 for epilogue (remember that we always need at least 4 epilogue warps to access all of Tensor memory).

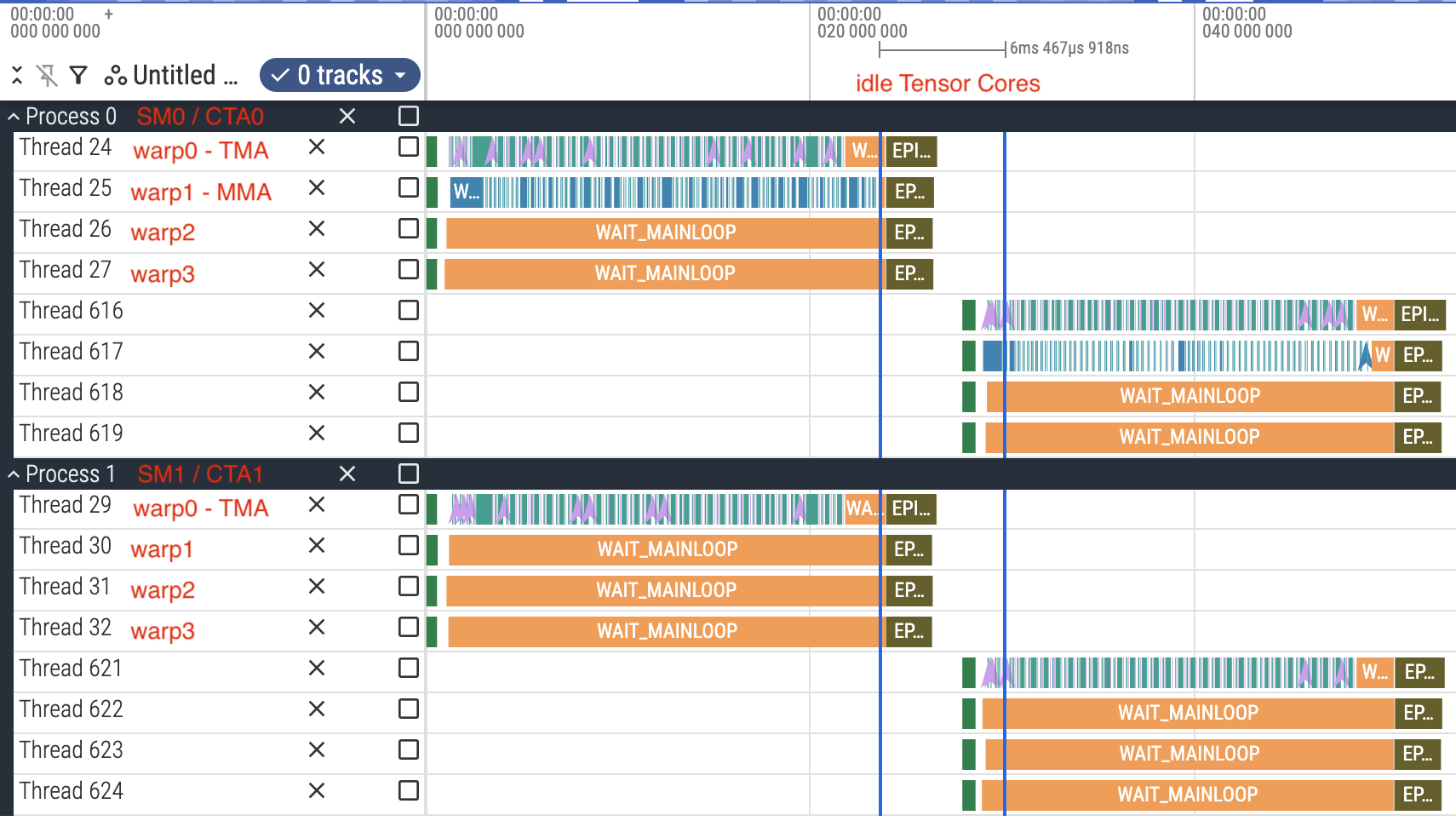

matmul_v6.cu produces this beauty.

Intra-kernel profile of kernel v6. Source: profile_v5.json.gz.

The epilogue-TMA/MMA overlap is not perfect according to the trace above, perhaps due to the presence of the profiler, but the TMA / Tensor Cores idle time is significantly reduced. This brings us to 98% of CuBLAS speed!

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v5 (2-SM MMA) | 1302.29 |

| v6 (persistent w/ static scheduling) | 1475.93 |

Closing remarks

Let’s take a look at our iterations.

| Kernel name | TFLOPS |

|---|---|

| CuBLAS (PyTorch 2.9.1 + CUDA 13) | 1506.74 |

| v1a (basic tcgen05 + 2D 16B TMA) | 254.62 |

| v1b (3D 16B TMA) | 252.81 |

| v2a (2D 128B TMA) | 681.20 |

| v2b (3D 128B TMA) | 695.43 |

| v3 (pipelining) | 939.61 |

| v4 (warp specialization) | 1208.83 |

| v5 (2-SM MMA) | 1302.29 |

| v6 (persistent w/ static scheduling) | 1475.93 |

We haven’t managed to beat CuBLAS, but it is not the goal of this mini-advanture. I only want to understand the basic (and slightly advanced) usage of tcgen05, in which we have achieved. I would not be surprised that with a few extra tricks (we even haven’t added threadblock swizzling for better L2 utilization, or Blackwell Cluster Launch Control), we can be faster than CuBLAS. This is left as a good exercise for the interested readers.

I also want to leave some of my observations here. Thanks to the specialized hardware and its associated instructions, I do feel Tensor Cores programming on Blackwell is easier than that on the previous generations. Once you kinda know what’s expected to achieve good FLOPS, the design space is somewhat small. You can mostly think of the problem at the tile level instead of thread level. Consequently, there aren’t much mental gymnastics around calculating thread addresses (we don’t even need to compute swizzling!), except a simple one in the epilogue. But I think this may pose some challenges when mixing tcgen05 with CUDA-core operations (e.g. attention), because synchronization between the generic and async proxies is probably quite expensive. Flash Attention 4 is probably a good case study for this.

Finally, I want to give credits to:

- DeepGEMM, which was my main reference for the kernel structure and the usage of certain PTX instructions. I’m sure there is a Zhihu blog somewhere explaining the codebase that I don’t know about.

- Modular Blackwell series, providing the missing explanations for a lot of important

tcgen05concepts.