Writing Speed-of-Light Flash Attention for 5090 in CUDA C++

In this post, I will walkthrough how I learned to implement Flash Attention for 5090 in CUDA C++. The main objective is to learn writing attention in CUDA C++, since many features are not available in Triton, such as MXFP8 / NVFP4 MMA for sm120. I also feel this is a natural next step after learning about matmul kernels. Lastly, there are many excellent blogposts on writing fast matmul kernels, but there is none for attention. So I want to take this chance to write up something nicely.

Readers are highly recommended to be familiar with CUDA C++ and how to use Tensor cores on NVIDIA GPUs. Of course you can still read along and clarify with your favourite LLMs along the way. Or you can check out GPU-MODE series (slides, YouTube) for basic CUDA C++ knowledge, as well as the excellent matmul blogposts mentioned above, to quickly get up to speed.

You can find the full implementation discussed in this post here: https://github.com/gau-nernst/learn-cuda/tree/e83c256/07_attention. For bs=1, num_heads=8, len_query=4096, len_kv = 8192, 5090 @ 400W, compile with CUDA 12.9, I obtained the following benchmark results (theoretical limit of 5090 is 209.5 TFLOPS for BF16)

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

F.sdpa() (Flash Attention) | 186.73 | 89.13% |

F.sdpa() (CuDNN) | 203.61 | 97.19% |

flash-attn | 190.58 | 90.97% |

| v1 (basic) | 142.87 | 68.20% |

| v2 (shared memory swizzling) | 181.11 | 86.45% |

| v3 (2-stage pipelining) | 189.84 | 90.62% |

v4 (ldmatrix.x4 for K and V) | 194.33 | 92.76% |

| v5 (better pipelining) | 197.74 | 94.39% |

Do note that although I only use Ampere features in these implementations (sm120 supports cp.async.bulk i.e. TMA, but I don’t use it here), my implementations might not run performantly on earlier generations of GPUs. Due to improvements in newer hardware, you might need to use more tricks to reach Speed-of-Light on older GPUs e.g. pipeline shared memory to register memory data movements.

Flash Attention algorithm

Let’s start with the reference implementation of attention.

from torch import Tensor

def sdpa(q: Tensor, k: Tensor, v: Tensor):

# q: [B, Lq, DIM]

# k: [B, Lk, DIM]

# v: [B, Lk, DIM]

D = q.shape[-1]

scale = D ** -0.5

attn = (q @ k.transpose(-1, -2)) * scale # [B, Lq, Lk]

attn = attn.softmax(dim=-1)

out = attn @ v # [B, Lq, DIM]

return out

Technically, if the inputs are BF16, some computations should remain in FP32, especially softmax. However, for brevity, we omit them.

We are implementing the algorithm outlined in the Flash Attention 2 paper. Each threadblock is responsible for a chunk of Q, and we will iterate along the sequence length of KV. A Python-like outline of the algorithm looks like below (S and P follow Flash Attention notation).

scale = DIM ** -0.5

for b_idx in range(B):

for tile_Q_idx in range(Lq // BLOCK_Q):

### start of each threadblock's kernel

tile_O = torch.zeros(BLOCK_Q, DIM)

tile_Q = load_Q(b_idx, tile_Q_idx) # [BLOCK_Q, DIM]

for tile_KV_idx in range(Lk // BLOCK_KV):

# first MMA: S = Q @ K.T

# (BLOCK_Q, DIM) x (BLOCK_KV, DIM).T -> (BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV)

tile_Q # (BLOCK_Q, DIM)

tile_K = load_K(b_idx, tile_KV_idx) # (BLOCK_KV, DIM)

tile_S = tile_Q @ tile_K.T # (BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV)

tile_S = tile_S * scale

# online softmax and rescale tile_O

...

# second MMA: O = P @ V

# (BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV) x (BLOCK_KV, DIM) -> (BLOCK_Q, DIM)

tile_P # (BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV)

tile_V = load_V(b_idx, tile_KV_idx) # (BLOCK_KV, DIM)

tile_O += tile_P @ tile_V # (BLOCK_Q, DIM)

# normalize output and write results

store_O(b_idx, tile_Q_idx)

### end of each threadblock's kernel

It’s implied DIM is small, so that we can hold tile_Q in register memory throughout the duration of the kernel. This is the reason pretty much all models nowadays use head_dim=128. There are exceptions of course, like MLA, which uses head_dim=576 for Q and K, and head_dim=512 for V. Talking about this, I should study FlashMLA some day.

Online softmax is quite tricky to explain, so let’s delay the explanation of that part. At the high level, you just need to know that online softmax will transform tile_S to tile_P, and also rescale tile_O.

Version 1 - Basic implementation

We will follow the typical MMA flow

- Load a 2D tile of data from global memory to shared memory using cp.async. This requires Ampere (sm80 and newer).

- Load data from shared memory to register memory using ldmatrix.

- Call mma.m16n8k16 for BF16 matrix multiplication (and accumulate).

I want to focus on implementing the algorithm correctly first, hence I leave out more complicated tricks like shared memory swizzling and pipelining. This reduces the surface area for mistakes, and we will revisit them later for performance optimization.

Global to Shared memory data transfer

The following templated function does a 2D tile copy from global memory to shared memory.

- Shape of the 2D tile is specified via

HEIGHTandWIDTH. dstis shared memory address,srcis global memory address.- Global memory

srcis row-major, sosrc_stridespecifies how much to move to the next row. - Shared memory

dstis also row-major, and will be stored as a contiguous block ->dst_stride = WIDTH.

#include <cuda_bf16.h>

template <int HEIGHT, int WIDTH, int TB_SIZE>

__device__ inline

void global_to_shared(uint32_t dst, const nv_bfloat16 *src, int src_stride, int tid) {

constexpr int num_elems = 16 / sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

constexpr int num_iters = HEIGHT * WIDTH / (TB_SIZE * num_elems);

for (int iter = 0; iter < num_iters; iter++) {

const int idx = (iter * TB_SIZE + tid) * num_elems;

const int row = idx / WIDTH;

const int col = idx % WIDTH;

const uint32_t dst_addr = dst + (row * WIDTH + col) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

const nv_bfloat16 *src_addr = src + (row * src_stride + col);

asm volatile("cp.async.cg.shared.global [%0], [%1], 16;" :: "r"(dst_addr), "l"(src_addr));

}

}

2D tile copy from Global memory to Shared memory.

We will use inline assembly to write cp.async.cg.shared.global. This PTX does 16-byte transfer, or 8 BF16 elements (num_elems = 16 / sizeof(nv_bfloat16)), for each CUDA thread. To ensure coalesced memory access, consecutive threads will be responsible for consecutive groups of 8xBF16.

Consecutive threads are responsible for consecutive groups of 8xBF16.

Note:

- The loop

for (int iter = 0; iter < num_iters; iter++)is written this way so that the compiler (nvcc) can fully unroll the loop.num_itersis known at compile time (guaranteed byconstexpr). If we mixtidin the loop, which is a “dynamic” variable to the compiler, the loop can’t be unrolled, even when we know certain constraints about the variable i.e.tid < TB_SIZE. - Data type of shared memory pointer

dstisuint32_t. This is intentional. Pretty much all PTX instructions expect shared memory addresses to be in shared state space. We can convert C++ pointers, which are generic addresses, to shared state space addresses withstatic_cast<uint32_t>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(ptr)). This is done outside ofglobal_to_shared().

To finish using cp.async, we also need to add the following:

cp.async.commit_group(PTX): commit all previously issuedcp.asyncinstructions into acp.asyncgroup. This group will be the unit for synchronization.cp.async.wait_all(PTX): wait for all committed groups to finish.__syncthreads(): make sure all threads (in a threadblock) reach here before reading the loaded data in shared memory (because one thread may read data loaded by another thread). More importantly, this broadcasts visibility of the new data to all threads in the threadblock. Without__syncthreads(), the compiler is free to optimize away memory accesses.

As always, refer to PTX doc for more information about the instructions. Basically we issue multiple cp.async and wait for them to complete immediately right after. commit_group and wait_group provide a mechanism for us to implement pipelining later. But for now, just need to know we have to write it that way to use cp.async.

Our code snippet would look something like this.

// nv_bfloat16 *Q;

// uint32_t Q_smem;

// const int tid = blockIdx.x;

// constexpr int TB_SIZE = 32 * 4;

// constexpr int DIM = 128;

global_to_shared<BLOCK_Q, DIM, TB_SIZE>(Q_smem, Q, DIM, tid);

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;");

asm volatile("cp.async.wait_all;");

__syncthreads();

Shared memory to Register memory data transfer

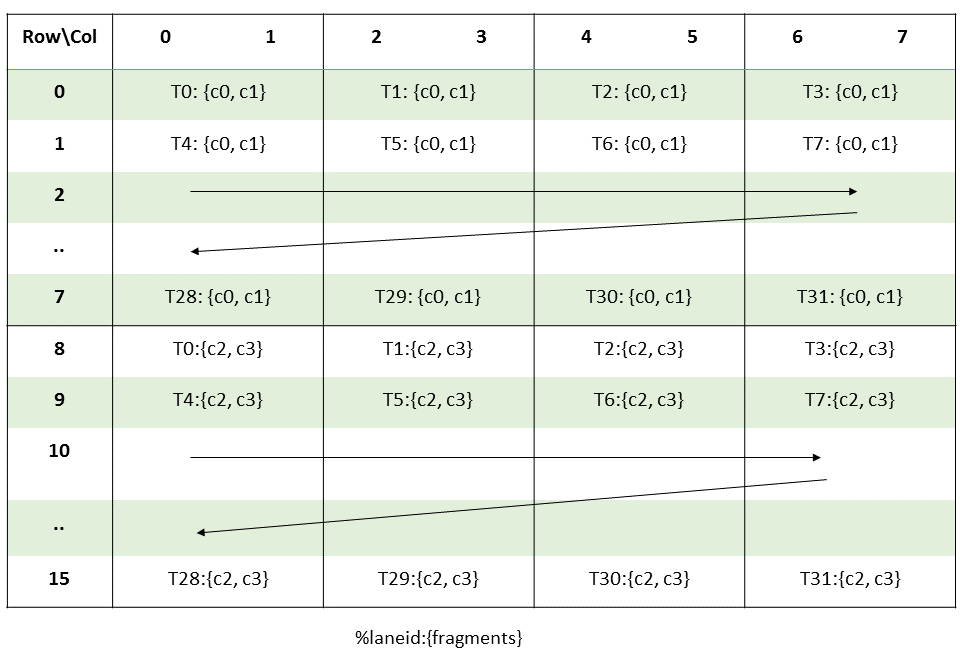

When doing global->shared data transfer, we think in terms of threadblock tiles and individual CUDA threads. For shared->register data transfer, since this is to service later MMA instructions, we think in terms of warp tiles/MMA tiles and warps. Following Flash Attention 2 (section 3.3), we let each warp in a threadblock handle a portion of tile_Q, splitting along the Q sequence length dimension. This means that different warps will index into different chunks of tile_Q, but they all index to the same tile_K and tile_V chunks in the KV-sequence-length loop.

Warp partition in Flash Attention 2.

Since we are using mma.m16n8k16 instruction, each MMA 16x8 output tile (m16n8) requires 16x16 A tile (m16k16) and 8x16 B tile (n8k16). ldmatrix can load one, two, or four 8x8 tile(s) of 16-bit elements. Hence,

- A tile

m16k16requires four 8x8 tiles ->ldmatrix.x4 - B tile

n8k16requires two 8x8 tiles ->ldmatrix.x2

Only Q acts as A in an MMA. Both K and V act as B in their MMAs, though K will require transposed ldmatrix for correct layout (all tensors use row-major layout in global and shared memory).

To use ldmatrix, each thread supplies address of a row. Threads 0-7 select the 1st 8x8 tile, threads 8-15 select the 2nd 8x8 tile, and so on. The layout of A in the official PTX documentation can look confusing. But it’s easier (at least for me) to focus on the order of 8x8 tiles within an MMA tile.

Order of ldmatrix tiles in mma.m16n8k16.

With the visualisation above, I hope the following snippet makes sense

constexpr int MMA_M = 16;

constexpr int MMA_N = 8;

constexpr int MMA_K = 16;

uint32_t Q_smem;

uint32_t Q_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][DIM / MMA_K][4];

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_K; mma_id_d++) {

const int row = (warp_id * WARP_Q) + (mma_id_q * MMA_M) + (lane_id % 16);

const int col = (mma_id_d * MMA_K) + (lane_id / 16 * 8);

const uint32_t addr = Q_smem + (row * DIM + col) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

ldmatrix_x4(Q_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d], addr);

}

- The two nested loops tile

[MMA_M, MMA_K](i.e.[16, 16]) over[WARP_Q, DIM]in shared memory. (warp_id * WARP_Q)selects the warp tile. We don’t need this for K and V.(mma_id_q * MMA_M)inrowand(mma_id_d * MMA_K)incolselects the MMA tile.(lane_id % 16)inrowand(lane_id / 16 * 8)incolselect the correct row address for each thread, following the required Multiplicand A layout (see the figure above).

ldmatrix_x4() is a small wrapper around ldmatrix.sync.aligned.m8n8.x4.b16 PTX for convenience. You can refer to common.h for more details.

K and V can be loaded from shared to register memory similarly. One thing to note is about the row-major / column-major layout when using ldmatrix. Regardless of whether .trans modifier is used, each thread still provides the row address of each row in 8x8 tiles. .trans only changes the register layout of ldmatrix results.

Use transposed version of ldmatrix for V.

One trick to know whether to use the transposed version of ldmatrix is to look at the K-dim or the reduction dimension. The 1st MMA’s K-dim is along DIM dimension, while the 2nd MMA’s K-dim is along the BLOCK_KV dimension.

Draft version

We have the high-level tile-based design, and know how to load the data for MMA. Calling MMA is simple - just drop mma.sync.aligned.m16n8k16.row.col.f32.bf16.bf16.f32 PTX in our code. Our draft version looks like this.

constexpr int BLOCK_Q = 128;

constexpr int BLOCK_KV = 64;

constexpr int DIM = 128;

constexpr int NUM_WARPS = 4;

constexpr int TB_SIZE = NUM_WARPS * 32;

// mma.m16n8k16

constexpr int MMA_M = 16;

constexpr int MMA_N = 8;

constexpr int MMA_K = 16;

__global__

void attention_v1_kernel(

const nv_bfloat16 *Q, // [bs, len_q, DIM]

const nv_bfloat16 *K, // [bs, len_kv, DIM]

const nv_bfloat16 *V, // [bs, len_kv, DIM]

nv_bfloat16 *O, // [bs, len_q, DIM]

int bs,

int len_q,

int len_kv) {

// basic setup

const int tid = threadIdx.x;

const int warp_id = tid / 32;

const int lane_id = tid % 32;

// increment Q, K, V, O based on blockIdx.x

...

// set up shared memory

// Q_smem is overlapped with (K_smem + V_smem), since we only use Q_smem once

extern __shared__ uint8_t smem[];

const uint32_t Q_smem = __cvta_generic_to_shared(smem);

const uint32_t K_smem = Q_smem;

const uint32_t V_smem = K_smem + BLOCK_KV * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

// FA2: shard BLOCK_Q among warps

constexpr int WARP_Q = BLOCK_Q / NUM_WARPS;

// set up register memory

uint32_t Q_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][DIM / MMA_K][4]; // act as A in MMA

uint32_t K_rmem[BLOCK_KV / MMA_N][DIM / MMA_K][2]; // act as B in MMA

uint32_t P_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][BLOCK_KV / MMA_K][4]; // act as A in MMA

uint32_t V_rmem[BLOCK_KV / MMA_K][DIM / MMA_N][2]; // act as B in MMA

float O_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][DIM / MMA_N][4]; // act as C/D in MMA

// Q global->shared [BLOCK_Q, DIM]

global_to_shared<BLOCK_Q, DIM, TB_SIZE>(Q_smem, Q, DIM, tid);

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;");

asm volatile("cp.async.wait_all;");

__syncthreads();

// Q shared->register. select the correct warp tile

// Q stays in registers throughout the kernel's lifetime

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_K; mma_id_d++) {

const int row = warp_id * WARP_Q + mma_id_q * MMA_M + (lane_id % 16);

const int col = mma_id_d * MMA_K + (lane_id / 16 * 8);

const uint32_t addr = Q_smem + (row * DIM + col) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

ldmatrix_x4(Q_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d], addr);

}

__syncthreads();

// main loop

const int num_kv_iters = len_kv / BLOCK_KV;

for (int kv_idx = 0; kv_idx < num_kv_iters; kv_idx++) {

// accumulator for the 1st MMA. reset to zeros

float S_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][BLOCK_KV / MMA_N][4] = {}; // act as C/D in MMA

// load K global->shared->registers [BLOCK_KV, DIM]

// similar to loading Q, except we use ldmatrix_x2()

...

// 1st MMA: S = Q @ K.T

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++)

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_K; mma_id_d++)

mma_m16n8k16(Q_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d],

K_rmem[mma_id_kv][mma_id_d],

S_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_kv]);

// online softmax. we will touch on this later

// also pack S_rmem to P_rmem for the 2nd MMA

...

// load V global->shared->registers [BLOCK_KV, DIM]

// similar to loading K, except we use ldmatrix_x2_trans()

...

// 2nd MMA: O += P @ V

// similar to the 1st MMA

...

// increment pointer to the next KV block

K += BLOCK_KV * DIM;

V += BLOCK_KV * DIM;

}

// write output

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_N; mma_id_d++) {

const int row = warp_id * WARP_Q + mma_id_q * MMA_M + (lane_id / 4);

const int col = mma_id_d * MMA_N + (lane_id % 4) * 2;

float *regs = O_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d];

reinterpret_cast<nv_bfloat162 *>(O + (row + 0) * DIM + col)[0] = __float22bfloat162_rn({regs[0], regs[1]});

reinterpret_cast<nv_bfloat162 *>(O + (row + 8) * DIM + col)[0] = __float22bfloat162_rn({regs[2], regs[3]});

}

}

// kernel launcher

void attention_v1(

const nv_bfloat16 *Q, // [bs, len_q, DIM]

const nv_bfloat16 *K, // [bs, len_kv, DIM]

const nv_bfloat16 *V, // [bs, len_kv, DIM]

nv_bfloat16 *O, // [bs, len_q, DIM]

int bs,

int len_q,

int len_kv) {

// 1 threadblock for each BLOCK_Q

const int num_blocks = bs * cdiv(len_q, BLOCK_Q);

// Q overlap with K+V.

const int smem_size = max(BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV * 2) * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

// use dynamic shared memory so we can allocate more than 48kb if needed.

if (smem_size > 48'000)

CUDA_CHECK(cudaFuncSetAttribute(kernel, cudaFuncAttributeMaxDynamicSharedMemorySize, smem_size));

attention_v1_kernel<<<num_blocks, TB_SIZE, smem_size>>>(Q, K, V, O, bs, len_q, len_kv);

CUDA_CHECK(cudaGetLastError());

}

Now, let’s tackle online softmax.

Online softmax - Theory

For the original explanation, you can refer to Online normalizer calculation for softmax and Flash Attention 2 paper.

We have the following mathematical definition of softmax. For each row with length $L_{kv}$

$$ p_l = \frac{\exp(s_l-m)}{\exp(s_0-m) + \exp(s_1-m) + \dots + \exp(s_{L_{kv}-1}-m)} $$ $$ l\in[0,L_{kv}) $$ $$ m=\max(s_0,s_1,\dots,s_{L_{kv}-1}) $$

$-m$ is max subtraction to improve numerical stability ($\exp(\cdot)$ can easily explode if its input is large). Let’s bring out the denominator normalizer and write the whole row as a vector.

$$ \vec P = \begin{bmatrix} p_0 \\ \vdots \\ p_{L_{kv}-1} \end{bmatrix} = \frac{1}{\sum_{l\in[0,L_{kv})}\exp(s_l-m)} \begin{bmatrix} \exp(s_0-m) \\ \vdots \\ \exp(s_{L_{kv}-1}-m) \end{bmatrix} $$

In our 2nd matmul O += P @ V, each row of P (softmax output) is dot-producted with the corresponding column of V.

$$ o=\vec P \cdot \vec V = \frac{1}{\sum_{l\in[0,L_{kv})}\exp(s_l-m)} \sum_{l\in[0,L_{kv})}\exp(s_l-m) \cdot v_l $$

The extra dot-product is a blessing in disguise - we no longer need individual elements in a row for the final result. This enables Flash Attention to compute attention in one pass. To see it more clearly, let’s consider the iterative process of adding a new element during online computation.

$$ o_{[0,L)} = \frac{1}{\sum_{l\in[0,L)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L)})} \sum_{l\in[0,L)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L)}) \cdot v_l $$ $$ m_{[0,L)}=\max(s_0,s_1,\dots,s_{L-1}) $$

I’m abusing the notation here, but I hope I get the idea across. When we add a new element $s_{L+1}$

$$ o_{[0,L+1)} = \frac{1}{\sum_{l\in[0,L+1)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L+1)})} \sum_{l\in[0,L+1)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L+1)}) \cdot v_l $$

Look at the normalizer (denominator)

$$ \sum_{l\in[0,L+1)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L+1)}) = \colorbox{red}{$\displaystyle\exp(m_{[0,L)}-m_{[0,L+1)})$}\colorbox{orange}{$\displaystyle\sum_{l\in[0,L)}\exp(s_l-m_{[0,L)})$} + \colorbox{lime}{$\displaystyle\exp(s_L-m_{[0,L+1)})$} $$

The equation means that we only need to $\colorbox{red}{rescale}$ the $\colorbox{orange}{previous normalizer}$ before adding the $\colorbox{lime}{new term}$. The same logic can be applied for the dot product with V (unnormalized output). This is the key idea of online softmax and Flash Attention.

Define attention state

$$ \begin{bmatrix} m \\ \tilde{o} \\ \mathrm{sumexp} \end{bmatrix} $$

where $m$ is the max of elements seen so far, $\tilde{o}$ is the unnormalized output, and $\mathrm{sumexp}$ is the normalizer. We need $m$ to compute the rescaling factor as seen above.

You can convince yourself that updating attention state is an associative operation - it does not matter the order in which elements are used to update the attention state.

$$ \begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} m_1 \\ \tilde{o}_1 \\ \mathrm{sumexp}_1 \end{bmatrix} \oplus \begin{bmatrix} m_2 \\ \tilde{o}_2 \\ \mathrm{sumexp}_2 \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} m_3 \\ \tilde{o}_3 \\ \mathrm{sumexp}_3 \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \max(m_1,m_2) \\ \exp(m_1-m_3)\tilde{o}_1+\exp(m_2-m_3)\tilde{o}_2 \\ \exp(m_1-m_3)\mathrm{sumexp}_1+\exp(m_2-m_3)\mathrm{sumexp}_2 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} $$

This associative property enables things like Flash Decoding, a split-K version of attention.

Online softmax - Implementation

We can now fill in the gap of online softmax in our high-level Python implementation.

# attention state

m = torch.zeros(BLOCK_Q)

tile_O = torch.zeros(BLOCK_Q, DIM)

sumexp = torch.zeros(BLOCK_Q)

for _ in range(Lk // BLOCK_KV):

# 1st MMA

tile_S = tile_Q @ tile_K.T # [BLOCK_Q, BLOCK_KV]

tile_S = tile_S * scale

# online softmax

tile_max = tile_S.amax(dim=-1) # [BLOCK_Q]

new_m = torch.maximum(m, tile_max)

tile_P = torch.exp(tile_S - new_m.unsqueeze(-1))

# rescale

scale = torch.exp(m - new_m)

tile_O *= scale.unsqueeze(-1)

sumexp = sumexp * scale + tile_P.sum(dim=-1)

m = new_m # save new max

# 2nd MMA

tile_O += tile_P @ tile_V # [BLOCK_Q, DIM]

# apply normalization

tile_O /= sumexp.unsqueeze(-1)

Row max

When translating this to CUDA C++, the most tricky part is to wrap our head around MMA layout. Let’s start with tile_S.

Thread and register layout of MMA m16n8k16 output. Source: NVIDIA PTX doc.

Softmax scale applies the same scaling for all elements, so that is trivial. Next, we need to compute row max for the current tile. Remember that we allocate the registers for tile_S this way.

float S_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][BLOCK_KV / MMA_N][4];

4 means c0,c1,c2,c3 in the figure above i.e. each thread holds 2 consecutive elements from 2 rows. To do reduction within a row (of an MMA output tile), we do reduction for 2 consecutive elements held by a thread, then reduction within a group of 4 threads i.e. T0-T3, T4-T7, and so on. However, the row reduction is actually within the whole tile_S, hence we also need to loop over BLOCK_KV / MMA_N of S_rmem. This can be combined with thread-level reduction before 4-thread reduction.

Perform row reduction on MMA output.

// initial attention state

float rowmax[WARP_Q / MMA_M][2];

float rowsumexp[WARP_Q / MMA_M][2] = {};

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++) {

rowmax[mma_id_q][0] = -FLT_MAX;

rowmax[mma_id_q][1] = -FLT_MAX;

}

// main loop

const int num_kv_iters = len_kv / BLOCK_KV;

for (int kv_idx = 0; kv_idx < num_kv_iters; kv_idx++) {

// tile_S = tile_Q @ tile_K.T

S_rmem[][] = ...

// loop over rows

for (int mma_id_q = 0; mma_id_q < WARP_Q / MMA_M; mma_id_q++) {

// apply softmax scale

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++)

for (int reg_id = 0; reg_id < 4; reg_id++)

S_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_kv][reg_id] *= softmax_scale;

// rowmax

float this_rowmax[2] = {-FLT_MAX, -FLT_MAX};

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++) {

float *regs = S_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_kv];

this_rowmax[0] = max(this_rowmax[0], max(regs[0], regs[1])); // c0 and c1

this_rowmax[1] = max(this_rowmax[1], max(regs[2], regs[3])); // c2 and c3

}

// butterfly reduction within 4 threads

this_rowmax[0] = max(this_rowmax[0], __shfl_xor_sync(0xFFFF'FFFF, this_rowmax[0], 1));

this_rowmax[0] = max(this_rowmax[0], __shfl_xor_sync(0xFFFF'FFFF, this_rowmax[0], 2));

this_rowmax[1] = max(this_rowmax[1], __shfl_xor_sync(0xFFFF'FFFF, this_rowmax[1], 1));

this_rowmax[1] = max(this_rowmax[1], __shfl_xor_sync(0xFFFF'FFFF, this_rowmax[1], 2));

}

...

}

In a typical reduction kernel, when there are only 32 active threads left, we can use warp shuffle __shfl_down_sync() to copy data from higher lanes to lower lanes, and the final result is stored in thread 0. In this case, since we need the max value to be shared among the 4 threads in a group (for max subtraction later), we can use __shfl_xor_sync() to avoid an additional broadcast step.

Butterfly reduction within 4 threads using __shfl_xor_sync().

Rescaling

With row max of the new tile, we can compute rescaling factor for (unnormalized) output as well as normalizer (sumexp of each row).

// new rowmax

this_rowmax[0] = max(this_rowmax[0], rowmax[mma_id_q][0]);

this_rowmax[1] = max(this_rowmax[1], rowmax[mma_id_q][1]);

// rescale for previous O

float rescale[2];

rescale[0] = __expf(rowmax[mma_id_q][0] - this_rowmax[0]);

rescale[1] = __expf(rowmax[mma_id_q][1] - this_rowmax[1]);

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_N; mma_id_d++) {

O_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d][0] *= rescale[0];

O_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d][1] *= rescale[0];

O_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d][2] *= rescale[1];

O_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_d][3] *= rescale[1];

}

// save new rowmax

rowmax[mma_id_q][0] = this_rowmax[0];

rowmax[mma_id_q][1] = this_rowmax[1];

We don’t rescale rowsumexp here because we want to fuse it with addition of the new sumexp term later i.e. FMA - fused multiply add. We can’t fuse multiplication with MMA, hence we need to do a separate multiplication for O_rmem.

Pack tile_S to tile_P (and compute row sum exp)

For the next part, we will loop over the row dimension again (BLOCK_KV / MMA_N), to compute and pack tile_P from tile_S, as well as doing reduction for sumexp. Recall that we declare registers for S and P as follows.

float S_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][BLOCK_KV / MMA_N][4] // m16n8

uint32_t P_rmem[WARP_Q / MMA_M][BLOCK_KV / MMA_K][4]; // m16k16

Look up the thread/register layout for MMA multiplicand A and output C/D again in PTX doc. Luckily, the layouts are exactly the same - within an 8x8 tile, the arrangement of elements is identical.

The left half of multiplicand A has the same layout as accumulator. Source: NVIDIA PTX doc.

It means that for all threads, every 2 floats in S_rmem can be packed as BF16x2 in a single 32-bit register of P_rmem, exactly how mma.m16n8k16 expects for the 2nd MMA. There are no data movements across threads. Note that this is not always true: if we use INT8 or FP8 MMA for the 1st and/or 2nd MMA, we would need to permute data across threads to pack tile_S to tile_P.

Our code for the last part of online softmax is below.

// rowsumexp

float this_rowsumexp[2] = {};

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++) {

float *regs = S_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_kv];

regs[0] = __expf(regs[0] - rowmax[mma_id_q][0]); // c0

regs[1] = __expf(regs[1] - rowmax[mma_id_q][0]); // c1

regs[2] = __expf(regs[2] - rowmax[mma_id_q][1]); // c2

regs[3] = __expf(regs[3] - rowmax[mma_id_q][1]); // c3

this_rowsumexp[0] += regs[0] + regs[1];

this_rowsumexp[1] += regs[2] + regs[3];

// pack to P registers for next MMA

// we need to change from m16n8 to m16k16

// each iteration of this loop packs half of m16k16

nv_bfloat162 *this_P_rmem = reinterpret_cast<nv_bfloat162 *>(P_rmem[mma_id_q][mma_id_kv / 2]);

this_P_rmem[(mma_id_kv % 2) * 2] = __float22bfloat162_rn({regs[0], regs[1]}); // top row

this_P_rmem[(mma_id_kv % 2) * 2 + 1] = __float22bfloat162_rn({regs[2], regs[3]}); // bottom row

}

// butterfly reduction on this_rowsumexp[2]

...

// accumulate to total rowsumexp using FMA

rowsumexp[mma_id_q][0] = rowsumexp[mma_id_q][0] * rescale[0] + this_rowsumexp[0];

rowsumexp[mma_id_q][1] = rowsumexp[mma_id_q][1] * rescale[1] + this_rowsumexp[1];

After this is the 2nd MMA: load V, then compute tile_O += tile_P @ tile_V. This completes our 1st version of Flash Attention. Actually we also need to normalize the output before writing O_rmem to global memory, but the logic for that should be pretty straightforward.

You can find the full code for Version 1 at attention_v1.cu.

Benchmark setup

Wow, that’s plentiful for the 1st version. Indeed, I spent the most time on version 1 trying to implement Flash Attention correctly. Took me 2 days to realize __shfl_xor_sync()’s mask should be 2 (0b10) instead of 0x10 for butterfly reduction.

Anyway, now we need a script for correctness check as well as speed benchmark. I prefer to do these things in Python Pytorch since it’s easy to do, as well as making it simple to compare against other attention kernels with PyTorch bindings. To achieve this, I create:

- attention.cpp: provides PyTorch bindings for my attention kernels.

- main.py: correctness check and speed benchmark.

For correctness check, I compare against F.sdpa(), which should dispatch Flash Attention 2 by default (at least on my GPU and current PyTorch version). I also purposely add a small bias to the random inputs, which are sampled from the standard normal distribution, so that the output has a positive mean. This is to avoid large relative error caused by zero mean.

def generate_input(*shape):

return torch.randn(shape).add(0.5).bfloat16().cuda()

For speed benchmarks, it’s generally a good idea to compare against (1) theoretical limit of the hardware i.e. Speed-of-Light, and (2) known good implementations. I’m more interested in the compute-bound regime of attention, hence I will be using FLOPS (floating point operations per second, with a capital S) as the metric for comparison.

To compute FLOPS of a given kernel, we count the number of required floating point operations (FLOPs, with a small s), then divide by the latency. Just counting FLOPs from the MMAs should be good enough, which turns out to be 4 * bsize * num_heads * len_q * len_kv * head_dim.

The “known good implementations” are FA2 and CuDNN backends of F.sdpa(), as well as FA2 from flash-attn package. For my kernel, I did do some tuning of BLOCK_Q and BLOCK_KV, and obtained the following results.

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

F.sdpa() (Flash Attention) | 186.73 | 89.13% |

F.sdpa() (CuDNN) | 203.61 | 97.19% |

flash-attn | 190.58 | 90.97% |

| v1 (basic) | 142.87 | 68.20% |

It doesn’t look too bad for the first version, but we still have some headroom to go. That’s fine, because we still have a few tricks up our sleeves for the next versions. In fact, the tricks are exactly the same as the ones used in optimizing a matmul kernel.

Profiling

Before moving to the next version, I want to talk about profiling tools. I think it’s always a good idea to use profiling as the guide for optimization. Previously I only knew how to use ncu at a very basic level. Seeing so many people using Nsight Compute with cool diagrams, I decided to learn how to use it, and it was actually quite easy to use.

Nsight Compute can run on macOS with SSH access to another machine with NVIDIA GPU, which is exactly the setup I’m using right now (yes, I write code exclusively on my Macbook). If you are unfamiliar with Nsight Compute, I recommend watching a tutorial or two to get acquainted with it.

To enable source inspection feature, remember to pass -lineinfo to NVCC (see here), and enable “Import Source” in Nsight Compute.

Version 2 - Shared memory swizzling

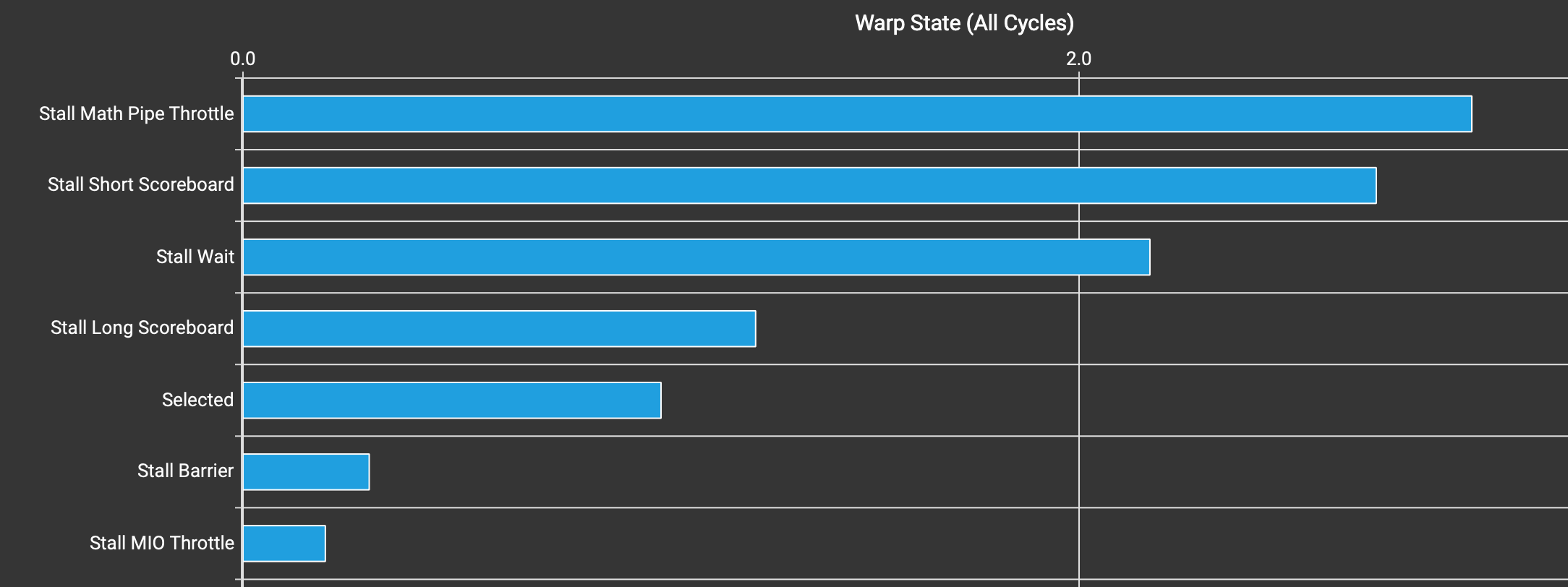

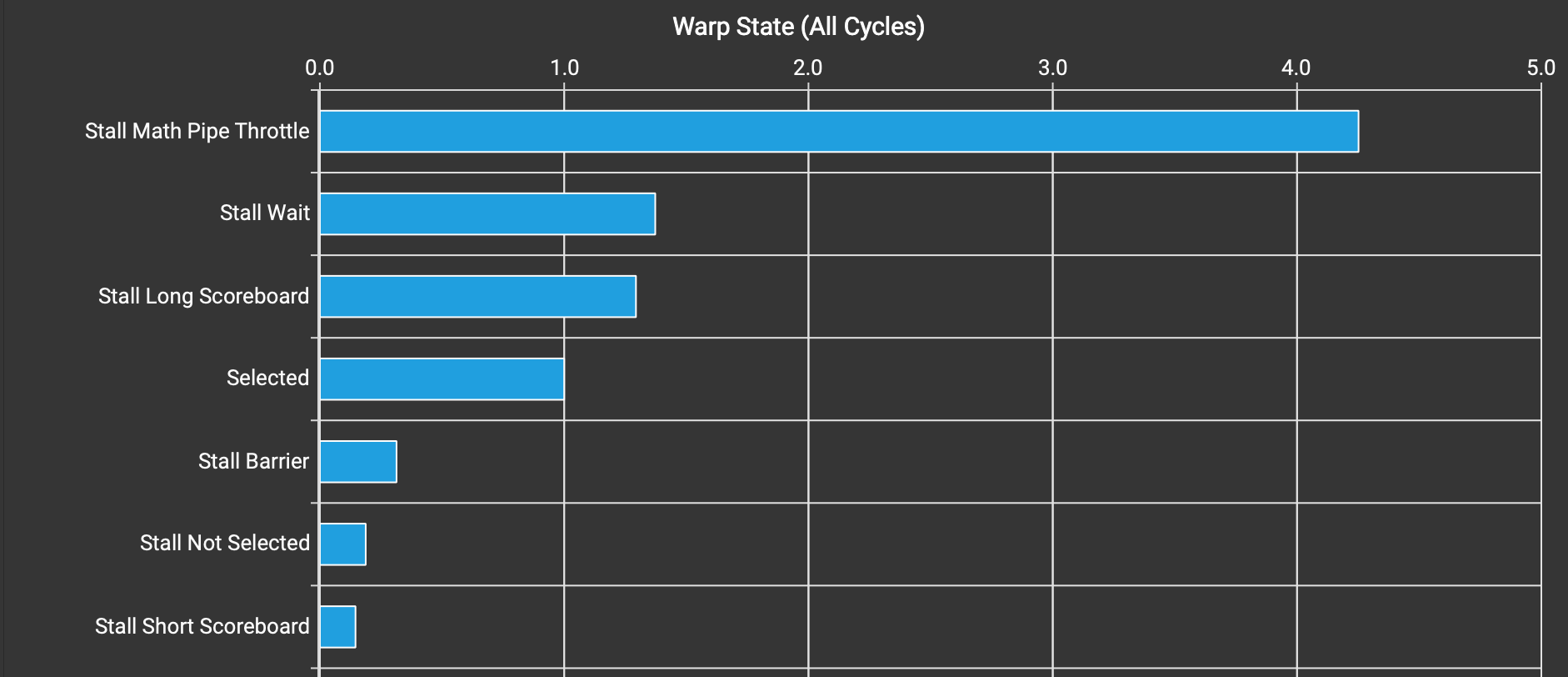

Let’s do a profiling with Nsight Compute, and look at Warp State Statistics section.

Warp state statistics of kernel v1.

Stall Math Pipe Throttle being the highest is good - it means warps are busy with math operations i.e. Tensor Cores. The second highest is Stall Short Scoreboard. This typically means waiting for accesses to and from shared memory. You can check Nsight Compute doc and search for stalled_short_scoreboard.

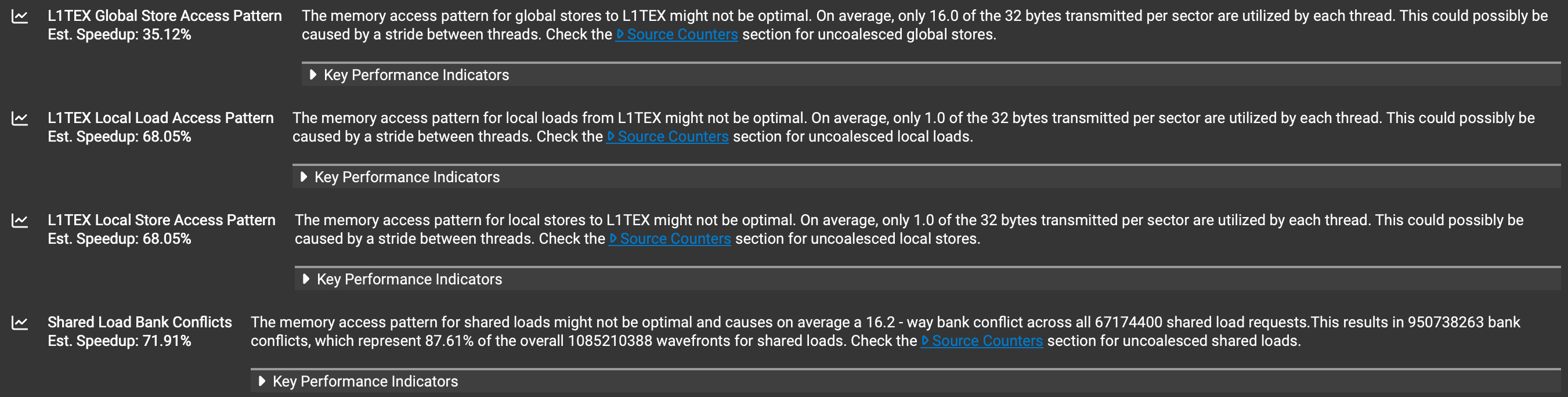

We can double confirm this by looking at Memory Workload Analysis, which reveals several problems.

Memory analysis of kernel v1.

- L1TEX Global Store Access Pattern comes from storing the output, since it is the only global write we have. This is not important since the runtime of looping over the sequence length of KV should dominate when

len_kvis large. - L1TEX Local Load/Store Access Pattern is due to register spilling. Since it’s register spilling, only spilling and reloading 1 element at a time is normal. Reducing

BLOCK_Q(so that we use fewer registers to hold accumulators) would resolve this issue, but my manual tuning showed that some spilling was actually faster. - Shared Load Bank Conflicts is exactly what we are looking for - bank conflicts that result in “Stall Short Scoreboard”.

NVIDIA GPU’s shared memory is backed by 32 memory banks. Consecutive 4-byte memory addresses are assigned to consecutive memory banks. This poses a problem when we load data from shared to register memory with ldmatrix. Although it’s not explitcitly stated in any documentations, ldmatrix.x2 and ldmatrix.x4 operate per 8x8 tile at a time. This is good, since it makes our analysis simpler: we only need to consider the case of loading a 8x8 tile.

Consider a 2D tile of shape 8x64, BF16 dtype, in shared memory.

Memory bank distribution for a 8x64 BF16 tile in shared memory.

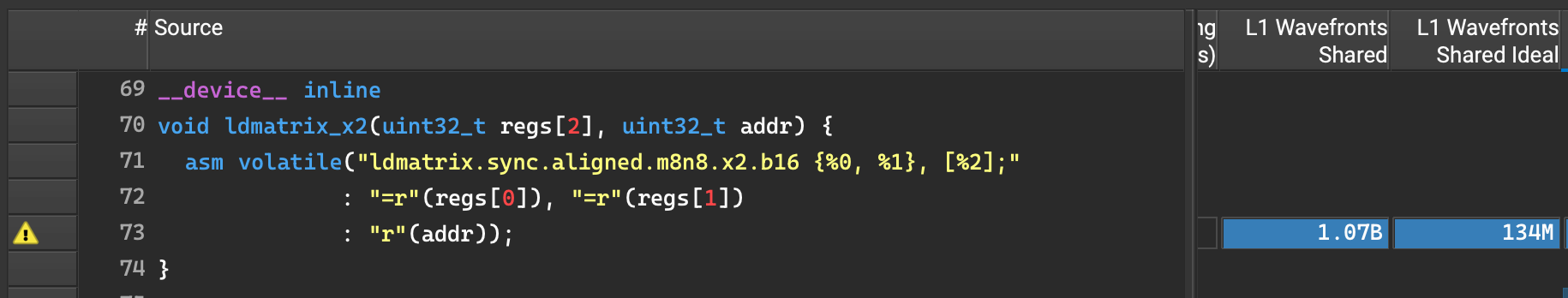

From the figure above, when we load the 8x8 ldmatrix tile, the same 4 banks 0-3 service all 32 threads, resulting in 8-way bank conflict. I’m not sure why Nsight Compute reports 16-way bank conflict as shown above. I tried looking up matmul blogposts with swizzling and NVIDIA forum threads, and found another way to check for bank conflicts was to go to the Source tab of Nsight Compute and check for L1 Wavefronts Shared and L1 Wavefronts Shared Ideal (I had to enable these two columns manually since they were not displayed by default for me).

Actual and Ideal L1 Wavefronts Shared of ldmatrix in kernel v1.

The ratio of Actual / Ideal is 8, matching our hypothesis of 8-way bank conflicts. I’m still not sure why there is a discrepancy between this value and the one in Details tab.

Anyway, there are 2 standard solutions to this problem

- Pad shared memory. Due to

ldmatrix’s alignment requirement, we can only pad the width with 16 bytes, equivalent to 4 banks. This means that when we go to the next row, the memory banks are shifted by 4, avoiding bank conflicts. In many cases, this is good enough. However, it’s generally quite wasteful as we are not utilising the padded storage. - Swizzle shared memory address. This is black magic: you XOR the shared memory address with some magic numbers, then suddenly bank conflicts disappear!

Let’s elaborate on the 2nd approach. I’m not smart enough to invent this trick, but at least I hope I can give some pointers on why it makes sense. We use XOR since this operation permutes the data nicely - there is a one-to-one mapping between input and output, given a fixed 2nd input. We get bank conflicts because when we move to the next row, we are hitting the same memory banks again -> we can use this row index to permute the addresses.

In particular, if we look at the raw row addresses:

- Bits 0-3 are always zeros due to 16-byte alignment constraint.

- Bits 2-6 determine bank index. We only need to care about bits 4-6 since the lower bits are always zeros (due to alignment).

- Row stride determines which bits are incremented when we move to the next row (this is by definition). If our 2D tile’s width is 64 BF16 elements, row stride is 128 bytes. Going to the next row will increment bit 7, leaving bits 0-6 unchanged (but we don’t care about bits 0-3).

- Thus, we can XOR bits 4-6 of row address with bits 0-2 of row index, which is guaranteed to change for every row.

If the tile width is different, e.g. 32 BF16, we can go through the same reasoning. Also notice that row index is encoded within the row address, thus we only need the row address and row stride to do swizzling.

// NOTE: stride in bytes

template <int STRIDE>

__device__

uint32_t swizzle(uint32_t index) {

// no need swizzling

if constexpr (STRIDE == 16)

return index;

uint32_t row_idx = (index / STRIDE) % 8;

uint32_t bits_to_xor = row_idx / max(64 / STRIDE, 1);

return index ^ (bits_to_xor << 4);

}

To enable this swizzling, we need to add it to cp.async (write to shared memory) and ldmatrix (read from shared memory) calls.

// for cp.async

- const uint32_t dst_addr = dst + (row * WIDTH + col) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

+ const uint32_t dst_addr = swizzle<WIDTH * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)>(dst + (row * WIDTH + col) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16));

asm volatile("cp.async.cg.shared.global [%0], [%1], 16;" :: "r"(dst_addr), "l"(src_addr));

// for ldmatrix

- ldmatrix_x2(K_rmem[mma_id_kv][mma_id_d], addr);

+ ldmatrix_x2(K_rmem[mma_id_kv][mma_id_d], swizzle<DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)>(addr));

Since this is a standard optimization in matmul kernels, I also added a small optimization for ldmatrix. I pre-compute row addresses and swizzling outside of the main loop, so that there is less work in the hot loop. When we iterate over MMA tiles within a warp tile, we need to increment the address. However, swizzling is a XOR operation, and we cannot simply exchange XOR with addition i.e. (a + b) ^ c != (a ^ c) + b. Notice that if there is some alignment in the base address a, addition becomes XOR! i.e. 100 + 001 == 100 ^ 001. Hence, when incrementing the input address of ldmatrix, we XOR it with column offset, instead of doing addition. Row offset will affect bits higher than the swizzled bits, so we can keep addition for it.

// K shared->registers

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_K; mma_id_d++) {

// swizzle(addr + offset) = swizzle(addr) XOR offset

uint32_t addr = K_smem_thread;

addr += mma_id_kv * MMA_N * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16); // row

addr ^= mma_id_d * MMA_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16); // col

ldmatrix_x2(K_rmem[mma_id_kv][mma_id_d], addr);

}

Version 2: attention_v2.cu.

We can verify that there are no more bank conflicts with Nsight Compute. Benchmark results show an impressive uplift (I always re-tune BLOCK_Q and BLOCK_KV for new versions of the kernel).

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

| v1 (basic) | 142.87 | 68.20% |

| v2 (shared memory swizzling) | 181.11 | 86.45% |

Version 3 - 2-stage pipelining

Warp state statistics of kernel v2.

Stall Short Scoreboard is no longer an issue, since we have handled it with swizzling. Now the issues are:

- Stall Wait (

stalled_waitin Nsight Compute doc): “waiting on a fixed latency execution dependency”, doesn’t seem to be a big issue. - Stall Long Scoreboard (

stalled_long_scoreboardin Nsight Compute doc): usually means waiting for global memory accesses.

Up until now, we haven’t overlapped global memory operations with compute operations (MMA). This means the Tensor Cores are idle while waiting for global->shared transfer to complete. This seems to be the right time to introduce pipelining or double-buffering: allocate more shared memory than needed so that we can prefetch data for the next iteration while working on the current iteration.

- Technically we can also pipeline shared->register data transfer. This is in fact mentioned in Efficient GEMM doc of CUTLASS. However, I could never implement it successfully on my 5090. Inspecting the generated SASS of my current code, I see that there is interleaving between

LDSM(ldmatrixin PTX) andHMMA(half-precisionmmain PTX), probably done by the compiler to achieve similar memory-compute overlapping effect.

Let’s discuss the more general implementation of N-stage pipelining. This NVIDIA blogpost gives a pretty good explanation of the idea, but generally I don’t really like using CUDA C++ API (and considering that CUTLASS also doesn’t, I think it’s more fun to use PTX directly). N-stage means there are N ongoing stages at any point in time. This will be the invariance we want to keep throughout the inner loop.

- This is the same concept of

num_stagesmentioned in triton.Config for autotuning. - Double buffering is a special case of N=2.

num_stages = 4

# set up num_stages buffers

tile_K_buffers = torch.empty(num_stages, BLOCK_KV, DIM)

tile_V_buffers = torch.empty(num_stages, BLOCK_KV, DIM)

# initiate with (num_stages-1) prefetches

# this is async: the code continues before data loading finishes.

for stage_idx in range(num_stages-1):

tile_K_buffers[stage_idx] = load_K(stage_idx)

tile_V_buffers[stage_idx] = load_V(stage_idx)

for tile_KV_idx in range(Lk // BLOCK_KV):

# prefetch tile (num_stages-1) ahead

# now we have num_stages global->shared inflight.

# in practice, we need to guard against out of bounds memory access.

prefetch_idx = tile_KV_idx + num_stages - 1

tile_K_buffers[prefetch_idx % num_stages] = load_K(prefetch_idx)

tile_V_buffers[prefetch_idx % num_stages] = load_V(prefetch_idx)

# select the current tile

# we need a synchronization mechanism to make sure data loading

# for this tile has finished.

# this "consumes" the oldest global->shared inflight, and

# replaces it with a compute stage.

tile_K = tile_K_buffers[tile_KV_idx % num_stages]

tile_V = tile_V_buffers[tile_KV_idx % num_stages]

# compute attention as normal

...

NVIDIA engineers/architects have graced us with cp.async.commit_group and cp.async.wait_group to implement this elegantly.

cp.async.commit_group: onecp.asyncgroup maps naturally to one prefetch stage in the pipeline.cp.async.wait_group N: means wait until there are at most N ongoing groups left. If we docp.async.wait_group num_stages-1, it means we wait until the earliest prefetch has finished (remember, we always havenum_stagesongoing prefetches as the loop invariance).

In our case of implementing attention, there are two small changes.

- Since we already consume a lot of shared memory for K and V, and consumer GPUs typically have modest shared memory size compared to their server counterparts, I decide to keep it to 2-stage pipeline, which also makes the code slightly simpler.

- We can split K and V prefetches since issuing V prefetch can be delayed to after the 1st MMA. The second change requires some minor adjustments: each K and V prefetch is a separate

cp.asyncgroup (so that we can wait for them independently).

One neat coding style that I have learned from Mingfei Ma, the maintainer of PyTorch CPU backend, is to use lambda expression to write prefetch code. It achieves two benefits: (1) keep the relevant code close to the call site, and (2) make it very clean to call the same block of code multiple times.

const int num_kv_iter = cdiv(len_kv, BLOCK_KV);

auto load_K = [&](int kv_id) {

// guard against out-of-bounds global read

if (kv_id < num_kv_iter) {

// select the shared buffer destination

const uint32_t dst = K_smem + (kv_id % 2) * (2 * BLOCK_KV * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16));

global_to_shared_swizzle<BLOCK_KV, DIM, TB_SIZE>(dst, K, DIM, tid);

// load_K() will be in charge of incrementing global memory address

K += BLOCK_KV * DIM;

}

// we always commit a cp-async group regardless of whether there is a cp.async

// to maintain loop invariance.

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;");

};

auto load_V = ...;

// prefetch K and V

load_K(0);

load_V(0);

for (int kv_id = 0; kv_id < num_kv_iter; kv_id++) {

// prefetch K for the next iteration

// now we have 3 prefetches in flight: K-V-K

load_K(kv_id + 1);

// wait for prefetch of current K to finish and load K shared->registers

// now we have 2 prefetches in flight: V-K

asm volatile("cp.async.wait_group 2;");

__syncthreads();

...

// 1st MMA

...

// prefetch V for the next iteration

// now we have 3 prefetches in flight: V-K-V

load_V(kv_id + 1);

// online softmax

...

// wait for prefetch of current V to finish and load V shared->registers

// now we have 2 prefetches in flight: K-V

asm volatile("cp.async.wait_group 2;");

__syncthreads();

...

// 2nd MMA

...

}

I experimented a bit with where to place load_K/V and cp.async.wait_group in the loop, and have found the above placement yielded the best performance. Although ultimately it depends on how the compiler rearranges and interleaves different instructions, the above placement makes sense: placing load_V() after the 1st MMA so that Tensor Cores can start working immediately when K data is in registers (instead of waiting for issuing V’s cp.async) i.e. keeping Tensor Cores busy; load_V() is placed before online softmax to keep memory engine busy (while CUDA cores are working on online softmax). Again, the optimal placement can also depend a lot on the hardware e.g. relative speed of memory and compute, whether different memory and compute units can work at the same time…

Version 3: attention_v3.cu.

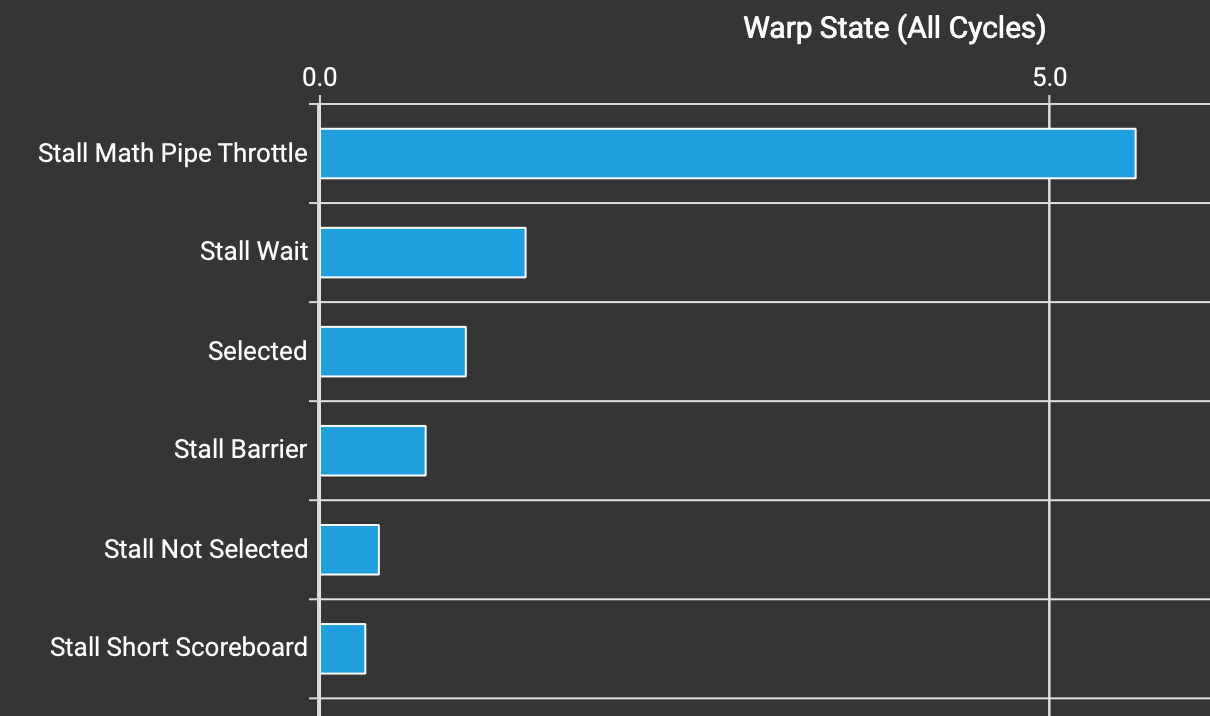

Warp state statistics of kernel v3.

Stall Long Scoreboard is now gone from Warp state statistics. I also had to reduce BLOCK_KV from 64 to 32 since we are using two buffers for K and V now, so that the total amount of shared memory usage remains the same.

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

| v2 (shared memory swizzling) | 181.11 | 86.45% |

| v3 (2-stage pipelining) | 189.84 | 90.62% |

Version 4 - ldmatrix.x4 for K and V

For the last two versions, I couldn’t identify any optimization opportunities from the profiling data (maybe just skill issue). The ideas mostly come from reading up random stuff and staring at the kernel.

Previously, we use ldmatrix.x2 for K and V since it naturally fits n8k16 MMA tile. However, since we are handling a larger tile anyway, we can directly use ldmatrix.x4 to issue fewer instructions. There are two options: load n16k16 tile, or n8k32 tile.

Possible options for using ldmatrix.x4 for multiplicand B.

Is one option better than the other? We can try doing some analysis in terms of arithmetic intensity. At first glance, n16k16 looks like a better option: 2 ldmatrix.x4 (1 for A and 1 for B) to do 2 mma.m16n8k16; while n8k32 option needs 3 ldmatrix.x4 (2 for A and 1 for B) to do 2 mma.m16n8k16. If we are to implement this idea for a matmul kernel, this analysis would make sense. However, in our case, multiplicand A (query) is already in registers, thus we only need to consider loading cost of multiplicand B (key and value). This realization shows that the two options should be the same.

You can definitely choose a different pattern to load K and V, but I hope at least the two options provided here are a bit more organized. To implement this idea, the key is to select the correct row addresses of 8x8 ldmatrix tiles.

{

// pre-compute ldmatrix address for K, using n8k32 option

// [8x8][8x8][8x8][8x8]

const int row_off = lane_id % 8;

const int col_off = lane_id / 8 * 8;

K_smem_thread = swizzle<DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16)>(K_smem + (row_off * DIM + col_off) * sizeof(nv_bfloat16));

}

for (int kv_id = 0; kv_id < num_kv_iter; kv_id++) {

...

// K shared->registers

// notice mma_id_d is incremented by 2

for (int mma_id_kv = 0; mma_id_kv < BLOCK_KV / MMA_N; mma_id_kv++)

for (int mma_id_d = 0; mma_id_d < DIM / MMA_K; mma_id_d += 2) {

uint32_t addr = K_smem_thread + (kv_id % 2) * (2 * BLOCK_KV * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16));

addr += mma_id_kv * MMA_N * DIM * sizeof(nv_bfloat16); // row

addr ^= mma_id_d * MMA_K * sizeof(nv_bfloat16); // col

ldmatrix_x4(K_rmem[mma_id_kv][mma_id_d], addr);

}

...

}

Version 4: attention_v4.cu.

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

| v3 (2-stage pipelining) | 189.84 | 90.62% |

v4 (ldmatrix.x4 for K and V) | 194.33 | 92.76% |

I was quite surprised at the speedup. The only difference in this version is that we use 2x fewer ldmatrix instructions in the main loop. Yet, we obtain a non-trivial improvement, inching towards SOL. I’m guessing since Tensor Cores and memory engine are so fast in newer GPUs, scheduling and issuing instructions can become a bottleneck!

Version 5 - better pipelining

In version 3, we use double buffers for both K and V. However, this is redundant: while doing the 1st MMA, we can prefect V for the current iteration; while doing the 2nd MMA, we can prefetch K for the next iteration. In other words, we only need double buffers for K.

// prefetch K

load_K(0);

for (int kv_id = 0; kv_id < num_kv_iter; kv_id++) {

// prefetch V for current iteration

// now we have 2 prefetches in flight: K-V

// __syncthreads() here is required to make sure we finish using V_smem

// from the previous iteration, since there is only 1 shared buffer for V.

__syncthreads();

load_V(kv_id);

// wait for prefetch of current K and load K shared->registers

// now we have 1 prefetch in flight: V

...

// 1st MMA

...

// prefetch K for the next iteration

// now we have 2 prefetches in flight: V-K

load_K(kv_id + 1);

// online softmax

...

// wait for prefetch of current V and load V shared->registers

// now we have 1 prefetch in flight: K

...

// 2nd MMA

...

}

Version 5: attention_v5.cu.

Using shared memory more efficiently means we can increase some tile sizes. I increased BLOCK_KV from 32 back to 64. Increasing BLOCK_Q is hard since it will double the amount of registers to hold the accumulator. The improvement is modest but noticeable.

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

v4 (ldmatrix.x4 for K and V) | 194.33 | 92.76% |

| v5 (better pipelining) | 197.74 | 94.39% |

What’s next?

| Kernel | TFLOPS | % of SOL |

|---|---|---|

F.sdpa() (Flash Attention) | 186.73 | 89.13% |

F.sdpa() (CuDNN) | 203.61 | 97.19% |

flash-attn | 190.58 | 90.97% |

| v1 (basic) | 142.87 | 68.20% |

| v2 (shared memory swizzling) | 181.11 | 86.45% |

| v3 (2-stage pipelining) | 189.84 | 90.62% |

v4 (ldmatrix.x4 for K and V) | 194.33 | 92.76% |

| v5 (better pipelining) | 197.74 | 94.39% |

Looking back, our kernel v3 already beats the official Flash Attention kernel, which is a nice surprise. It feels like it’s rather easy to get good performance out of 5090 compared to previous generations. However, our best kernel lagging behind CuDNN’s means that there is still headroom available. I tried inspecting profiling data of CuDNN’s attention kernel, and got the following details

- Kernel name:

cudnn_generated_fort_native_sdpa_sm80_flash_fprop_wmma_f16_knob_3_64x64x128_4x1x1_kernel0_0-> I’m guessing it means using sm80 features,BLOCK_Q=BLOCK_KV=64,DIM=128, and 4 warps (same as our kernel v5). - Shared memory: 40.96 Kb -> that is

40960 / (64 * 128 * 2) = 2.5times(BLOCK_KV, DIM). The fractional number of buffers is rather strange. Or is their kernel more likeBLOCK_KV=32and 5 buffers? I have no idea.

Anyway, here are some fun ideas to build on top of this (apart from trying to beat CuDNN):

- Implement the backward pass (which I heard is much harder than the forward pass)

- Quantized/low-bit attention, especially with NVFP4 on 5090. I believe SageAttention is the open-source frontier on this front.

- Use TMA (i.e.

cp.async.bulk) with warp-specialization design. Pranjal wrote a nice blogpost on this for H100 matmul. - PagedAttention (i.e. vLLM and SGLang), and then build a performant dependency-free serving engine.

I hope this blogpost is useful to many people. Happy writing kernels!